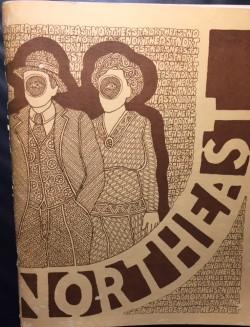

Opening couple of pages of a novel-in-flash, written in 1969 or so, excerpt published in Northeast, 1974. Certainly can detect the influence of Nathanael West’s The Dream Life of Balso Snell here, not his greatest. Call this juvenilia, included here for its discoveries re form.

The word ‘tessellation’ comes from the tesserae in a mosaic: a tessellation is one tile. The Pn business has something to do with Probability distribution, I forget what. It seemed smart and sexy at the time, and how can anyone resist an exclamation point in math?

I kept the skewed-focus modifier in the second sentence because it seemed child-like, and speaking of, note the echoes of ‘a moocow coming down along the road,’ where, in a couple of paragraphs, my Stephen hero will catch up with a nicens biggish nanny named Nursie, and off they’ll debark into a sea of me. West and even more so Joyce were enduring influences on me, when I started out at Iowa once upon a time, and a very good time it was . . . .

I’d like to say something about the history of this form, experimental back in the 1960s, but I already have too long an introductory. Maybe at the bottom; for now, an opening snap-shot of an early novella-in-flash, or if not quite ‘stand-alone’ flashes, certainly varied fragments.

If enough is already enough, can return to where you were, from here: Author

TESSELLATIONS

Pn , n = n!

Nursie’s drowned.

Sleepy still, looking at the ocean, flat as a lake, it seemed she had done something wrong.

“Is she dead, too?”

“Yes, darling, someone’s who’s drowned has to be dead.” Daddy was in a boat in the navy.

“Will Daddy drown?”

“If Daddy’s ship sank, he might. But it won’t.”

Why not. “Why not, Mommy?”

“Fish drown,” Dana said, nudging one with his brown toe that over-reached his sandal,

~~adjusting ornaments on the festoons of seaweed~~

“Fish drown of air,” he said.

It was nice then, walking on that early beach with the two tall people, Dana naming fish and shells, Dana who drew me pictures of Things—an eagle with a monkey’s head, and sheeted ghosts with shiny shoes peeping out from under. Dana whom mother called over when I had the appendix, or for Christmas, and who was already there earlier that morning when the police arrived to tell mother about Nursie.

[If it isn’t obvious yet, it soon will be, that Dana is sleeping over, and the dawn arrival of the police to report Nursie’s suicide has compromised the two adults. All that the boy catches onto, though, is ‘Mother was mad at Nursie for drowning.’]

Nursie drowned, and a new word that attached to the moon that lingered on the other side of the sky, attached there as I looked there to remember it, slipped from horn to horn of that thinnest of moons, slid till nearly halved, dangled off: suilcide.

Nursie had drowned of suilcide.

Daddy might in the navy.

Dana of a time had shown me a picture in the newspaper of suilcide—a moussilini, hanging upside down, barely, by the bar on the l in suilcide.

One thing was clear: Mother was mad at Nursie for drowning.

*

Another dawn soon after, not on that ocean where German U-Boats were spotted, but on the canal by hour house, where it was lunchtime when the tide was in, rising to push me away from the seawall, deepening all my pleasures out of reach, the stone crabs and crawfish, and anemones my gig bisected and quartered like Nursie’s fork bearing down on my food, which tide had withdrawn by half again by the time lunch and nap were over, which dawn coaxed me to leave my room and descend the only quiet path down the stairs and walk as only one can when first in the morning, the grass stirring and me but for my bare feet scraping the earthworms on the flagstones in two, moving among splinters out onto the dock, three-pronged gig in hand, I saw Nursie floating down the canal among the flotsam, coconuts and rubbers and jellyfish and palm fronds, all standard targets for the gig, and Nursie in her white uniform like a soggy piece of bread, but too far out until I threw…thund…rolling her face up and so pointing the gig down, which pulled out on my first tug but drifted her near enough to the dock that, armed with my gig I boarded, secured, ready for anything with that triton, three of the fingers of my entire childhood.

An I arrive at your door? Gig in one hand like Ulysses inland with his oar, string in other attached to my musical pull-along Nursie: a child lost but between the fact and the knowledge of it, please, take me in?

*

[It cuts away to a present time wife here, having a terrible time with a large hallucinated reptile, from one of the children’s dinosaur books, while to calm her the husband reads from the want ads in the farmer’s section (this is Iowa, after all).]

“Spotted Poland China Boars,” pause. “Wet sows wanted. Will pay premium. Two hundred fifty gallon anhydrous applicator.”

It was working, she was calming, dabbing more reflectively, setting the spilled sugar crystals in a pattern on the table top.

“Gehl chopper, with all three heads. Wanted, colon, unclaimed and orphaned lambs.”

She stopped dabbing, which meant for him to go back: “Wanted, colon, unclaimed—“

“No,” she said. “Before that.”

But here the table rose, ludicrous like a camel, and shivered its skin free of the sugar.

“ ’Lo, ole boy,” she said, resignedly, patting his flank, which was thin and taut as a cured covered wagon. “Good reptile,” pat, stroke, but he of course read the fondle forensically, its weight, its somehow non-touch, and her husband, still at the table, asked, “Reptile?” and scanned what he’d read for anything like a reptile. Gehl chopper maybe, with three heads. With the paper before him as a kind of cow-catcher, he followed her into the living room.

*

Nursie’s eyes blink open-shut when the water washes over her face, her head tips back so far. The neck stretch forces her mouth open, a perfect mast head. So foot on her chin I step the butt of the my gig (having already attached her tongue as a wind sock) and tie her apron to the out-rigged gig points. Before the wind, downhill on the out-going tide, we make thrilling time.

We scud along over the pocked bay, pausing, circling a chamber now and then to look down, and in.

A maelstrom! This page can’t handle it, but Poe was at the bottom tossed in the froth of all that lint. Dana, as well as my father, was a naval man.

Some of these cubicles are filled with boxes of my toy soldiers—I recognize a few—they have individual faces painted on. But other cells are cluttered with things I’ve never seen before—pieces of paper on the floor, arcs of foot prints on them, with writing I’m not quite close enough to read, though one read, Is there anything we haven’t seen before?

*

Another pore, a large rectangular one, and on one wall, in a color of Georgia clay, is a bison, and opposite was my epitaph.

. . . [ ] . . .

Excerpted from:

Excerpted from:

Northeast: Special Experimental Fiction Issue, Edt. George Chambers. Summer 1974.

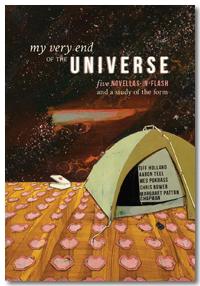

In a solid and informative 300 page book put together by Rose Metal Press, My Very End of the Universe: Five Novellas-in-Flash, and a Study of the Form (2014), edited by Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney, are collected five novellas-in-flash, with commentary by the authors, to wit: creating a full narrative from fragments; maps, secrets, spaces in-between; breaking the pattern to make the pattern; how subject dictates narrative form; mimicking memory in flash novellas.

This is as a good as it gets, so far, if you’re starting out or have one in progress. Plus a 20 page introduction by the editors on the history of the form. And looking to describe the interplay between the two genres—the short short and the novella—Abigail and Kathleen (as they go by in correspondence) come up with, to my mind, a right handy metaphor for the form: the stars. They stand alone, “as singular sparks of light, each one possessed of its own flickering beauty.” You can tell what’s coming: constellations! We’ve always named the stars, they say, “…and then taken those beloved luminous points and connected them in the sky into shapes and stories.” The pricks of light become the dots to connect: “…writers linking their flashes together into a larger image—into narratives deep with possibilities.” One of the contributors allows as how she didn’t even know she was writing a novella, in-flash, until she saw the call from Rose Metal Press for submissions. She’d just fallen in love with some characters and their worlds. She was able to merge that morass into a larger embracing, even more meaningful story.

This is as a good as it gets, so far, if you’re starting out or have one in progress. Plus a 20 page introduction by the editors on the history of the form. And looking to describe the interplay between the two genres—the short short and the novella—Abigail and Kathleen (as they go by in correspondence) come up with, to my mind, a right handy metaphor for the form: the stars. They stand alone, “as singular sparks of light, each one possessed of its own flickering beauty.” You can tell what’s coming: constellations! We’ve always named the stars, they say, “…and then taken those beloved luminous points and connected them in the sky into shapes and stories.” The pricks of light become the dots to connect: “…writers linking their flashes together into a larger image—into narratives deep with possibilities.” One of the contributors allows as how she didn’t even know she was writing a novella, in-flash, until she saw the call from Rose Metal Press for submissions. She’d just fallen in love with some characters and their worlds. She was able to merge that morass into a larger embracing, even more meaningful story.

Possibly you, dear reader, have some short shorts of yore, written over time, a few published perhaps, some languishing unfinished, some abandoned. I’d advise, read this Rose Metal book and then step out into your night sky. Who knows, maybe a meteor shower’s coming your way. It’s possible: the form continues to surprise me with its ingenious variations. And possibilities.

To that point: the editors of My Very End of the Universe, in their intro, establish that the form does have a history and tradition, “but they have been obscured by its lack of a name.” They reach back to Poe and Hawthorne, and then further to Boccaccio, Chaucer, Marguerite de Navarre’s Heptameron, then forward to Didion’s Play It As It Lays and Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street. But none of these is consciously creating stand-alone shorts also to be taken together in a full narrative arc, nodes of an implicit plot, not just providing a frame. Maybe Cirsneros does.

Yet there we were in the late sixties, doing just that. Chambers’ issue of Northeast that had my Tessellations, also had sections of Ron Sukenick’s endless postcard (“The Endless Short Story has a secret ambition it wants to write The Great American Postcard. These are some of the requirements . . .”); Jeanette Trouvé’s A Woman, which reads like the films Run, Lola, Run meets Momento; something by Dennis Mathis that’s all chopped up with * * *’s; some short Roman numeral’d pieces from Roland Topor’s The Shit of Knowledge; same thing from a Dave Kelly sequence; and my Tessellations . . .

Northeast’s ‘special experimental fiction issue’ was chock full of novellas-in-flash, in 1974, and all we could think to call them was experimental.

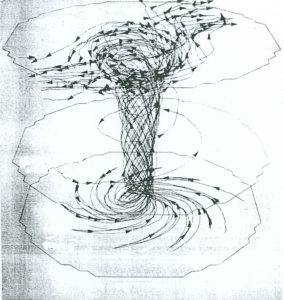

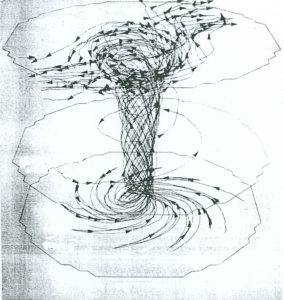

Jump forward forty years . . . My current novel-in-progress, The Islands, with groups of discrete characters mostly unaware of each other until they get sucked into a larger vortex and all come together at the end, is built up of short shorts along the lines of a model of a hurricane—the ‘parcels of air’ that accumulatively enter the system at the bottom, to spiral up the trunk to chaos at the top. I didn’t realize until I wrote this note, how much that work, of 2018 and forward, owes to my tesserae of 1968! The imagination print at work: the inescapable influence of oneself on oneself.

Moral: get to it, dear reader. A flash a day, will keep your constants in play. You can’t really avoid them, but your sure can improve upon them.

Return to: Author

Except, you know what? (What if an agent’s snooping around in here, you know? Are you with me?) I think I’ll include the opening flash of that novel. Notice the controlling metaphor—instead of tesserae, it’s chunks of concrete; instead of a mosaic, it’s an island, hatched by a hurricane:

THE ISLANDS

Miami Beach 1953

The Mounds

He was building out. Rock after rock, splash after splash, the boy wrestled the chunks of concrete down to the edge of the seawall to upend and tumble them into the greeny bay. Sploosh ka-thunk, the one-two punch of the broken chunk of sidewalk smacking the surface, the water displaced then closing fast with a concussive thunk, and some considerable spray. He leaped back because on certain days if the bay water touched you, it could eat into your flesh. Straight through to the bone.

When the bubbles cleared he saw he’d missed again. The slab hadn’t sunk into its proper niche, hadn’t locked into the mound like some of the chunks, fitting flush. He wiped his hands on his pants then sniffed his palms.

They were chalk-pale, coated in cement dust and cracked from the lime, dried out—sometimes they bled. A little picking, they’d bleed. They smelled of construction site, the dust kicked up into a chalky fog damping down the fumes of the diesel trucks backing in to dump the rubble with one man yelling above the engine noise, more men leaning around on shovels and picks, glistening shirtless in the sun. Men’s shirtless voices.