SHARKWALKER

Kent H. Dixon

The Florida Review, Summer 2012

These two women—classy office types, had to be in their mid-twenties, sporting smart outfits and bold make-up. Reese might have been eighteen, me still seventeen. They'd seen us glancing over. He leaned toward their table and said, "You girls are from New York, aren't you."

How could he tell, they wanted to know. So did I.

He shared: their clothes gave them away. New York women were sharp dressers.

They were interested. This was the height of the tourist season, Beautiful Miami Beach

of 1958 or so and they were looking for action, and Reese could smell it.

We joined them. By and by they sought to know more about us—about me out of courtesy, the focus was on him. After a spell, he filled them in. His was an unusual job—

Shark Walker, over at the new Seaquarium on Key Biscayne.

Eh?

Sure, the guy that guides the sharks around by their dorsal fins in a waist deep pool, to

get the water aerating through their gills again after they've been captured and transported in enclosed tanks. This needs be done else they'd suffocate; hence in the wild they always sleep in currents, else you'd get a lot of sudden shark death.

The girls were amused, almost believing—why not, this was Vacation. Reese, hand to his belt buckle, offered to show the bald patch on his thigh, hair worn off from rubbing up against sandpapery hides all day. Occupational hazard.

He had me believing it. Did he get a summer job last week, not tell me?

They dumped us finally, though do I remember one of them slipping him a matchbook, a folded bit of napkin?

How many stories have I tried to write about this adolescent chum, calling him Reed or Royce, or even Woody, E. Reese VanderWoude marking his own novelist phase. They never worked, those fictionalized memories, never any point besides the high adventure. Plenty of that, but no density, no mystery. And yet there is mystery. So now, four decades later, to it.

His name was a bit of a mystery. He said it came from the Peanut Butter Cup, like he was some kind of heir. That would get a snicker from us and he'd shrug. (He ate enough of them.) But it sounded like his mother called him Crees sometimes, harking back, he told me once, to French Canadian 'Cristino.' But one of his stepfathers hailed from Louisiana, so it was Cree from Creole, sometimes. In prep school, one of three or four, they often called him Speedo, as in the Cadillacs’ song, ...but my real name is Mis-ter Ea-rl. In fact, he was every bit the WASP that I was and pretty much looked it.

Am I suggesting he had an identity problem? I am not, though I don't really know. Certainly I did, but Reese always seemed dead right with whoever he was—preppy today, juvenile delinquent tonight. Acolyte at St. Pat's, escort of Miami Beach's finest debutantes, hospital lab technician, bar fly, Joe College in a buzz and white bucks (slightly scuffed). And not to forget Shark Walker, paramedic with the Jump Corps, movie producer's Finder, Frogman, Arthur Murray consultant—a specialist in "jig music" as we called it, hep if not enlightened. Our gang did a sleek dirty boogie to Sam Cook and Bobby Blue Bland when everyone else was discovering the jitterbug.

Reese was a little on the short side. Good build, something like the younger Paul Newman, Hud or Cool Hand Luke. Very fast off the mark, an important survival skill the way we played Miami Beach in the late 1950s. I can see him, penny loafer in each hand, slowing at the corner for me at the half-block with the bouncer, theater manager, wheezing cop, you name it, not far behind.

Washboard stomach, squarish pecs, shapely arms and forearms—a focus of my obsession with him, his forearms. Past fifty I still wear my sleeves half-rolled in forgotten imitation. But the little mouse that hopped its two-step between his elbow and mid-forearm never came to life in mine. We sport matching scars on our right forearms, mirror images of what on me looks like a displaced vaccination mark, from the burn we mutually acquired one drunken night, laying a lit cigarette between our parallel arms: who to pull away first? Neither of us did, and it stung like molten scorpion even if we were drunk—"Ooh, it smarts," chortles Reese—and the smell of burning flesh was grossing everyone out so we extinguished it between us, rolling one's arm against the other's as you'd grind a butt under your shoe. The attention far eclipsed the pain, and for me the resultant two-week, dime-sized, white and yellow pustule was a badge of victory. For me, to tie Reese was to beat him.

Hard enough to tie him—whether tennis or one-man volley ball in the sand; couldn't touch him in tag football on the beach, forget outrunning him, can't remember swimming—I wonder—I was fast for back then (the dolphin kick had just been invented: it blew away the frog kick). Do you suppose he demurred, over my butterfly?

He was a little bow-legged, that bouncy balls-of-the-feet walk of so many compact athletes—short legs, long waste. My knees are a mess today partly because I appropriated that just pigeon-toed, just slightly bowed bounce. I still love that walk in several of my young son's friends, as if the ground were just a resting place, these legs touch down only to push off, stay buoyant, give the earth a wee peck before moving on.

As I run all this back through, I have to admit the attraction seems as physical as it was anything else, sexual in most every way I can think of except nothing overt or active. Can't remember ever jerking off to thoughts of Reese, for example, but I sure must have gazed on him, sure took delight in his physique, his wit, his tan, his five o'clock shadow and smudge of mustache. His forearms. His fuck-ups, fearlessness, self-mocking irony. His sexy ways and not so boyish charm. His incredibly credible bull shit. His pretend laziness, his stutter; his somewhat insouciant efforts to educate me; his casual contributions to my health, wealth, and welfare—saved me money, made me money, saved my ass…saved my life once. The list goes on, it really does. If it wasn't sex, it sure enough was love.

I don't think he was actually handsome. I told my parents once I wished I were good looking, like Reese, and they laughed at me. But they were my parents. Didn't most of the girls I liked like him better? Wasn't that Judy locked in the closet one New Year's coaxing him to fill her shoe with champagne, and wasn't that Reese saying 'Let's use mine, it's bigger.' Fools. I loved each better than either ever would the other.

I remember consciously bringing some of my girl friends to him. Not for his approval, and not to share them, though that happened once or twice. Rather, it was a test: if they still preferred me after meeting him, then God help them: their lamb to my loins.

I said he stuttered. He didn't always, not at Miss Cushman's School, and then one summer, as if it had come in with his newly sharpened Adam's apple, he w'w'was s's'stut.. stuttering, and for several years thereafter he accented things cool by snapping his index finger—holding thumb to middle finger as if about to snap those two normally but then shaking the wrist so the index finger flapped down on the middle finger, snap snap snap, and this would help him halt the repeating syllable, or the catch in his throat before he could even get to that first syllable. We mocked him affectionately. I got so good at it—I think I really threw myself into this, an inner aspect of Reese that I could openly explore—g'g'got so good it nearly became my own ha' ah' (eyelid twitch, finger snap) handicap. When I'm around a stutterer for a few hours it seeps back, and I'm half inclined to let it. An old flame.

Reese was action, Reese was trouble: if he'd been one of my own sons' pals, fifteen years later, I would have minimized the contact. But he wasn't quite off-limits with my parents. They knew his mother and step-dad socially and assumed a good side, which I suppose he had—I envied his relationship with his younger sister, like Holden and Phoebe it seemed to me (the best part of that book the belching lessons), but it was this badness of his—hell raiser, dare devil, bullshit artist, ass man, catalyst for chaos—that made almost everything in my youth that was wildly fun, stupidly reckless, terribly destructive, fucking crazy, happen. Reese at the center, me and Sandy and PJ and sometimes Kurt or Tyler, in the shifting satellite positions, most of us with other groups of our own, none of these last named being my best friends really, just my trouble chums, or the ones that gravitated around him, so trouble was natural to our congregating. But not once do I remember running with any of them, anywhere, without Reese.

Like any set of wild ones, our bunch should by all rights, seriatim, be dead, with the exception of Reese, who should, by all the laws of physics and the seven mad gods of luck, have been cremated alive about twice a week. Catlike in more than quick reflexes, I will tell you.

The night—from one of his ninety-nine lives—he pulled the car over in the middle of the Baker's Haulover bridge and—this on a $10 bet—without hesitating vaulted the rail to the channel below. What's that, a hundred feet? We used to dare ourselves to jump from the top platform of the MacFadden Deauville tower, which was fifty feet high and made the acre of pool below look like a foot bath, and felt when you hit it like you'd stepped off water skis at 50 mph, and this Haulover bridge from its apex seemed twice as high as that. And the returning fishermen dump their day's unused bait and offal at the mouth, so sharks infest it. And the tides there... in a small boat you had to get a good head of steam up just to beat the currents when they opposed you. Ten horsepower might not always make it.

He told us he hit bottom. Someone said, You probably hit the top of one of those sunken freighters, you stupid shit. Lucky you weren't impaled.

Impaled? Lucky? He hadn't even looked before he leaped: reamed by a piling, or a barge could have been passing below, maybe some clown barnstorming his Piper Cub. Guy wires

crisscrossed everywhere on the sides, like a giant cheese slicer... Instead, a long half-minute later, there he was striking out for the shore on the back of the out-going tide. A Coast Guard boat picked him up; he told them he was a flagpole sitter (a fad at the time, revived from the 1930s), a professional flagpole sitter working the bridge tower, fell asleep, we up there waving and cheering at the railing were the news team or something, and he insisted they deliver him back to his perch. They took his name (he probably gave mine), and put him ashore.

Reese was believed. The claims, the bluffs… total strangers bought his reality and were quick to pay a surcharge, too. There were just the two of us in my ‘53 Chevy convertible, a sun-bleached yellow, black top, with yellow and black plaid vinyl seats (I loved that car, my first), cruising Collins Avenue, the year about 1957 (we're 16 and some), when an Olds or Buick with four college kids cuts us off. Middle fingers were given. Reese was driving (to give me my turn at the sidewalk palaver with the girls). He zooms after their car, pulls in front of it at a light, leaps out of the Chevy, strips off his jacket and slams it to the ground and says: Come on, mutha'-fuckers, I'll take you and you and you and you... And they rolled up their windows and locked their doors.

You tell me. He was charmed. Once when he totaled his mother's car, in a twisted batch of steel spliced around one or two other cars, he came around to the officer saying, 'Well, this one's sure dead.' Or so he told it; I missed that one but for the newspapers, and he did have his head shaved, with mucho stitches. Never had a fatal accident, he used to say. Snap, snap.

Christmas we were all home from our prep-schools, forming up again, climaxing in New Year's Eve festivities as if next day we'd be shipping out. One of these New Years, Reese got the tip of his nose bitten off in a fight. Just a quarter of an inch or so off the tip. We called the renowned plastic surgeon Raine Miller who lived nearby, and described the problem, offered to bring Reese right over.

"Don't bring him here," barked Miller into the phone. "Get him to the hospital. I'll meet you there. Bring the nose tip with you."

Shit, we couldn't find it. We called him back: no nose tip, but uh oh... There was this little yapping dog running around...

"If you can't find the nose bring the dog," said Miller.

Reese, painting the town, the street, his face, everything blood red, it just pulsing from his nose as they sped him across the St. Francis parking lot on a stretcher, shooting sedatives into his flailing arms, Reese putting his smartass face on it with a woozy, "Aw shit, man, I got better stuff than this at home."

We found the nose tip, by the bye. Someone had put it on the mantle piece though no one claimed to. The biter was out back sitting by the canal, arms around his knees rocking and intoning some personal mantra to the moon. Can't imagine he put it up there.

Nor did Miller reattach it quite right, and it started to die—the nose tip, rotting. Had to be trimmed and repositioned and riddled with antibiotics. For a week Reese went around saying, Something sure smells funny. What smells so funny?

Man, that's my kind of humor.

*

A caper I’ve never been able to skim off into fiction—I’ll spend it here. Larger than a caper, smaller than a déluge, though only by chance: the night we organized ourselves to take over a whorehouse. I'd discovered the hotel and knew the pimp had a gun, a .38 I suppose, something snub-nosed with a revolving chamber. Service revolver maybe. He'd shown it to me the week before when he'd invited me up to his hotel room for a drink. Care to explain that visit, Kent—sheer idiocy or just unmitigated death wish?

The pimp had noticed the out-of-county plates on my Chevy and so I'd told him—a momentary inspiration—that it was stolen. I was letting him know I wasn't just any punk rich kid (I lived about three blocks away on an exclusive residential island). Mean and seasoned, not to be messed with, me and my hot car (on loan for the summer by a friend of the family), looking to get laid that night. Might he know of any pussy about?

The pimp was solicitous, offered admonishments: watch myself, good looking kid like me, in prison... I'd get laid all right, and it took me a couple of beats to figure out it wasn’t his wallet he was patting. He'd done his time and nobody would ever fuck with him again and then he showed me why—the loaded .38 in the top bureau drawer, with the sock of extra bullets. Spun the chamber, snapped it shut, put it back. He wasn't to be messed with either, I guess.

No whores that night; all tied up, he said. But he offered me a consolation back rub; I demurred. Then he went out to get us cigarettes or a bottle (or a bigger fellow pimp is what I figured), and I sure wasn't there when they came back.

But a week or two later I returned in force, me and Reese, and Kurt and PJ and Sandy, and possibly one or two others—seems like there was quite a crowd of us, hard to manage—and after much crashing around in the hallways and trashing the room that two of us had rented, Sandy polishing off the second fifth of vodka and passing out though not before throwing up out the window, which had a screen in it—after such a couple of hours of just boys being boys, four of us finally caught up with the pimp in his room and announced we would be taking over his operation: three girls, one of them an extremely pretty brunette, like Veronica in the Archie comics, and the forty intervening years have not faded her name.

Ruthie, a shiny sulky sullen 21, she said, but we fancied she was 19; we were all 17 and 18. “Tougher ‘n Liz Taylor, kid,” the pimp had told me (this would be the Liz Taylor of Ivanhoe, pre-Eddie Fischer even—so don’t stoop to roll any eyeballs). So I'd hung out near the hotel, caught what could only be her in sunglasses ducking into a taxi, followed it to a bar on my bicycle (cutting corners like a madman), called Reese who met me there and we introduced ourselves, bought Tom Collinses for our threesome in a dingy corner lit like a clearing in a woods, the chairs all legs up on the table tops, the daylight cutting through from the open door, sticky antiseptic floor, Ruthie's heavy makeup at two in the afternoon. I remember this vividly because it was a kind of milestone: in the midst of it I caught myself thinking how absolutely neat, freeze this forever, please: I was utterly, perfectly happy.

Not so, Ruthie, not at all happy over the arrangements with her managers she told us on the second drink (she maintained she was a singer), so we planned to set her up in one of the houses left over from my childhood collection of broken and entered.

Bit of a side-bar gloss here: at 12, that age of accountability, I’d discovered I wanted to be a cat burglar when I grew up (somewhere in there between architect and psychiatrist), so I’d practiced on the neighborhood, twenty or thirty houses around the edge of the residential island I lived on, and I had a stretch of four or five I could traverse without ever touching the ground, entailing car hoods and curbstones and a lot of ad hoc rules, as well the neighbors' roofs while they slept in of a Sunday morning.

As some of these houses were closed for the off-season, eventually they yielded to my professional curiosity. A glass jalousie removed here, a screen door cut there: by age 15 I had two or three summer homes, de-fumigated, sheets removed from the furniture, rooms ready to play anything you wanted in—from hide-and-seek to date rape, which was thought of as a kind of natural persistence back then, by both parties.

I never invited Reese on any of these rooftop excursions when we were younger because, I think, they required a drop-off into make-believe (cat burglar, escaping convict, WWII commando, etc.), and Reese just wasn’t that kind of guy, even at 12 or 13. I never played toy soldiers with him either, for example, and I had the biggest collection around. It brings you to wonder about his fantasy track. Did he ever hear that silent music? Did he ever even need it?

Besides, what if he were to become a cop, as many a reformed crook has been known to do: he alone would know how to pursue me down the decades, like Inspector Javert after Jean Valjean. He alone would have my whammy. My inner jewel thief was possessed of wiser instincts.

So, a round-about explanation, not without its competitive edges I notice, of how at seventeen, the apprentice pimp/rookie cat burglar had houses to spare. We lacked only the whore.

Our plan for Ruthie was simple: set her up in the house I could just see through the ranks of nodding palm fronds outside my bedroom window, and we would bring her food, battery lamps, propane stove, bring her whatever she needed from our parents' hurricane gear, not to mention all our novice and curious, virginal and horny friends: she would not have to worry about disease. $20 a trick, say, or whatever the market would bear. She could set the price, and keep it all. Our only cut would be the freebees for ourselves.

Ruthie I don't think took us too seriously—she was being pestered and looked tired—to be that pretty and turning tricks she must have had a healthy habit, though maybe just business sense. Nonetheless, we thought we'd just surprise her. Get the 'horse' from our cop contacts; help her get clean. Get her on methadone, Reese said—he'd read William Burroughs by that point, I'm sure; give her, you know, some self-respect, a room of her own if not a life. We saw our plan as magnanimous actually, community service minded, albeit white slavery.

We were giving the pimp his walking papers that night when he edged for his bureau. I had told Reese about the gun. Reese caught my eye and my eye said Yes, and Reese sprang—had a silver chain-link, weaved-through-leather belt wound around his wonderful forearm and fist, his "New York wrap" he called it—and produced that gauntleted fist to stay the man; with his other hand he reached behind into the drawer and with absolutely no groping, lifted out the gun and emptied the bullets onto the floor.

"C’could this be what you're looking for?" he said, and I'm sitting on the bed watching my own private movie wondering, one, how long would it take for that guy to reload that gun if he got it away from us, and two, how many takes would it take to get it this right in a real movie? First try, behind his back, left hand straight to the .38, bullets spilling plock plock onto the carpet all in one seamless cinematic sweep. Such meshing, so smooth, my Reese.

As it turned out, the pimp did have a partner, who'd called the police, or maybe it was the bona fide residents of the hotel complaining—we'd done a fair amount of trundling through the halls—, but someone back in our room got wind of the change in our circumstances and up went the Hey,Rube, and out went the six of us, dragging along Sandy and the empty suitcase we'd checked in with—the only clear memory I have of this emergency exodus being some ill-lit and echoing cement stairwell and then sitting on the top of the back seat of Kurt's red Corvette which was the second and last of our two cars wheeling out of the parking lot to the right as half a block down the street to the left, three police cars lurched to a halt at the hotel's front entrance.

"Sit down, Francis!" shouts Kurt. "We'll get a fucking ticket!" the tires screeching in chorus with our Olympian laughter.

And the consequences of all this? Sandy's hangover, and one more night we didn't get laid.

*

We had a game: one guy holds out his hands in an attitude of prayer at waist level, facing the other guy hanging on to his own ear lobes, and then quicker than the prayer hands can be jerked away, the striker strikes. Loud smack, backs of hands get very red, sore to the bone. If you caught only air, the other guy's turn to strike at you. Reese was a master, of course.

You stare very hard into each other’s eyes in this hand-swatting—significance down to the twitch of an eyelash—and I remember letting him read, in the tea leaf speckles of our irises, that if the truth be known, I was crazier than he, that I'd always make a swell partner in crime, that if he wanted me, I'd be a fine first lieutenant. In fact, count on it, I would go where even he feared to tread.

It startles me to discover this next, but it may explain why he sometimes called me first, really about as often as my calling him: deep down, way below any flattery I felt at these intermittent So wha‘re ya doin’ today’s, unconscious to both of us really, could I have been the leader? Or, call it a tie again: could he have needed me as much as I him? He required an audience—I can't imagine him escapading alone; I was always surprised when he even mentioned a book, implying down time: what, a character that reads? He required his audience and I was surely that, and a loyal fan besides; but was I also an absentee manager of sorts, just happened to be sitting in the crowd that night, checking in on one of my hotter talents? Nothing I understood or controlled, mind—it wouldn't have worked if I had—but still, an essential grit in the cement of our friendship?

So many of the ideas were mine. Did I not bring him my whore? Did I not open up the best of my collection of neighborhood houses to him and our cronies? I brought him my bads as a cat deposits its dead mouse at your door, its highest honor I suspect, but still one that it confers.

I'd just as soon have skipped this next, but wasn't it my idea one fine mid-summer to kill someone?

The ultimate high they say, the same one Perry and Dick discovered back in the late 1950s when "in cold blood" they wiped out the whole Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas; one from that coroner's bag that no longer surprises us today—a wilding, a gratuitous proof, a life for a spot in a membership. Or maybe just for the sheer rush of it: waste someone. And I, middle class kid running in upper class circles—summer camps and private schools, sundry cars and before them my own speed boat (I water skied across the bay to school as an 8th grader, hid my boat in the reeds further up the canal); drinks from the right cabana boys at the country club

( —Hey, do we tip 'em? —Hell, no, it's their job.), escort in demand at all the gala social occasions, a regular at the debutante balls—there I was in 1958, of a mind with Perry and Dick.

Money, looks, brains, talent—why put to this use? With all that advantage, what goes awry? Hormones, that whole deck of wild cards, looking for a game? Officer Kromky, I've got a social disease? Ivan Karamazov: All is permitted? Homophobic love stories, expressed in crimson Valentines, little bloody nosegays of love and violence? I can't justify it and confession, "even a rag like this,” doesn't seem to absolve, and the implications discourage, to say the least: if the likes of me, how expect any better from a Blood or a Crip, or my own four sons even? (Is it genetic?)

I could blame my parents—who can't?—and their parents, and the whole dreary line of depressive alcoholics back to William the Conqueror or Gunga Din or whoever it is that tops one of those genealogy charts, but I needn't go that far. I could more readily indict the Second World War; it figures in, truly. A lot of people in Miami Beach never quite recovered from the eschatology of the Seventh Fleet's being stationed there—the last party—my parents among them.

And speaking of them, there is my father—sweet, affable, pickled man ruined by his mother, arrested in most aspects of his development around age fourteen, whereas I was born somewhere around fifteen and a half; it was a strange relationship. When I am being most paternal with my children, what comes out is based not on any model of my father's caring for me, but on my taking care of him, driving him home at 14, say, when even he thought he was 'too tight.'

Widening the focus to a blur, there's always today's scapegoat, the media: Truman Capote's In Cold Blood wouldn't be written for six more years, but we had our Brandos and Newmans, and before them Douglas père and Lancaster and "the Duke" (whom we dubbed a spondaic Silly - Old - Pooh), and for the record, you can't really leave out Sinatra and Tony Curtis and then Montgomery Clift and of course Jimmy Dean. "Marlon Brando's scowl and Elvis Presley's thrusting pelvis appeared to be telling their elders to get lost," writes Susan Faludi about the bad Bad Boy, in her recent book on men. "Get lost" did she say? Elvis' pelvis? Doesn't sound much like my Reese, my winsome shark, my amoral visionary, my load stone. When I wasn't actually with him, I was out building my own case. I was out there out-Reesing Reese.

Suffice it to say, I didn't want for heroes or initiative, but I sure could have used some direction. In prep school, with a forbidden flashlight in my closet or under the covers after lights out, all night sometimes, I read obsessively in search of a father, but I had a real flair for identifying the wrong way. I thought Holden Caulfield a tiresome twit; I wouldn't have sneaked into a movie with him; for me, Camus' affectless stranger was the un-phony one.

Though it's not really the books themselves, of course; it's the reader. Plato, you'll recall, banned youths from his Republic, on the grounds they would be corrupted by poetry. In my experience it's usually the other way round. I have taught 18 and 19 year olds too long not to appreciate how completely the breed can macerate the inner truth of a story, i.e., brashly and boldly miss the point and utterly transform the "meaning" of a work. (Those would be postmodern inverted commas; I do pass for an academic.)

One fond example of this perversion—theirs, not mine: in my office some years back a student was telling me with (for him) some enthusiasm about Hunter Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, where Thompson writes about the ultimate high, which according to the Gonzo Journalist author, is extract of human adrenalin, at $5000 a pop. Pretty powerful stuff, eh, doc? And I said well, yes, I supposed, but weren't there some problems with it, like the implication of murder, cannibalism, and so on, and my student stretched his legs, contemplated the pointed toes of his boots and sighed, "Yeah, but that's just fiction. The real bitch is the cost."

I don't think I've closed my door for conferences since. And yet, for all my promiscuous reading, was I any wit different? When my pal Wells took the trouble to send me from his military school a book he was really excited over, Clarence Darrow for the Defense, about the Leopold/Loeb murder trial, I figured, one, he'd found himself, was going to become a lawyer, wasn't that nice, and two, he was telling me something. I found a biography of Leopold and read around in his reading some, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer and such, and got back to Wells with what I thought was the import of all this: surely we were the supermen, morally super because, well, there really weren't any morals, and the way to test that or lock it in, or maybe just exercise this newly clarified entitlement, was to execute someone. Not some poor Bobby Franks kid, that was mean-spirited of them, but someone deserving, a criminal, a bad man, someone somewhere that might even want to do us harm; just let him try: would we ever have a surprise for him! Or maybe just someone that didn't matter, a bum or a derelict wino slumped in some ureal alley.

Wells was actually shocked, and wrote back that he'd meant for me to admire Mr. Darrow, not Nathan Leopold, and we would not talk of this again. We didn't. I moved on over to Reese. He and I developed a vague plan to go visit his father in Atlanta, who had a gun—they were harder to come by in those days—and we'd take that gun out of an evening and maybe someone would force us to use it on them, or maybe we'd just jolt them out of an alcoholic stupor, into the great beyond.

(Surely it's lost on no one—save me, till now, this paragraph actually—why I so had it in for alcoholic bums.)

Reese was more vague about this than I—he after all had played the musical stepfathers, in lieu of my good-as-absent one. Blurred his focus, perhaps. But I had a very concrete middle-aged, lean and grubby (and tall and lanky—my father was 6'5") wino in mind, a Bowery bum—in today's parlance, a street person. Homeless. I didn't want to hurt him, I didn't really want to kill him, certainly nothing personal, but some kind of ultimate drew me on, nothing flashy like brains and blood splattered on a wall; just a quiet though necessary bullet buried, splug, into worthless flesh—one of God's little scavengers, me, not even the implied sense of power in it, that I can recall. Just a deathless murder. Try anything once. Shrug and let die.

There was the notion of the perfect crime—but not a new idea for me. I'd been committing them for years: absolutely no doubt that I could get away with this one. Correction: no doubt we could get away with it; acting alone in this matter also had never occurred to me. Perry and Dick, neither one without the other, went the psychological pronouncement at the time. Kent and Reese. Kent and anyone, anyone for mad dog Kent?

The best explanation I've seen for all this comes from literary criticism: "male homosocial desire," how, according to Eve Sedgewick and now many others, men love to love each other through women. The collective visit to the brothel would be emblematic. I'd add violence to the mix, probably sports, any road to intimacy really (from the pat on the butt in front of the fans to the pre-wedding bachelor party on the edge of town), that in its buffered state keeps manhood in tact.

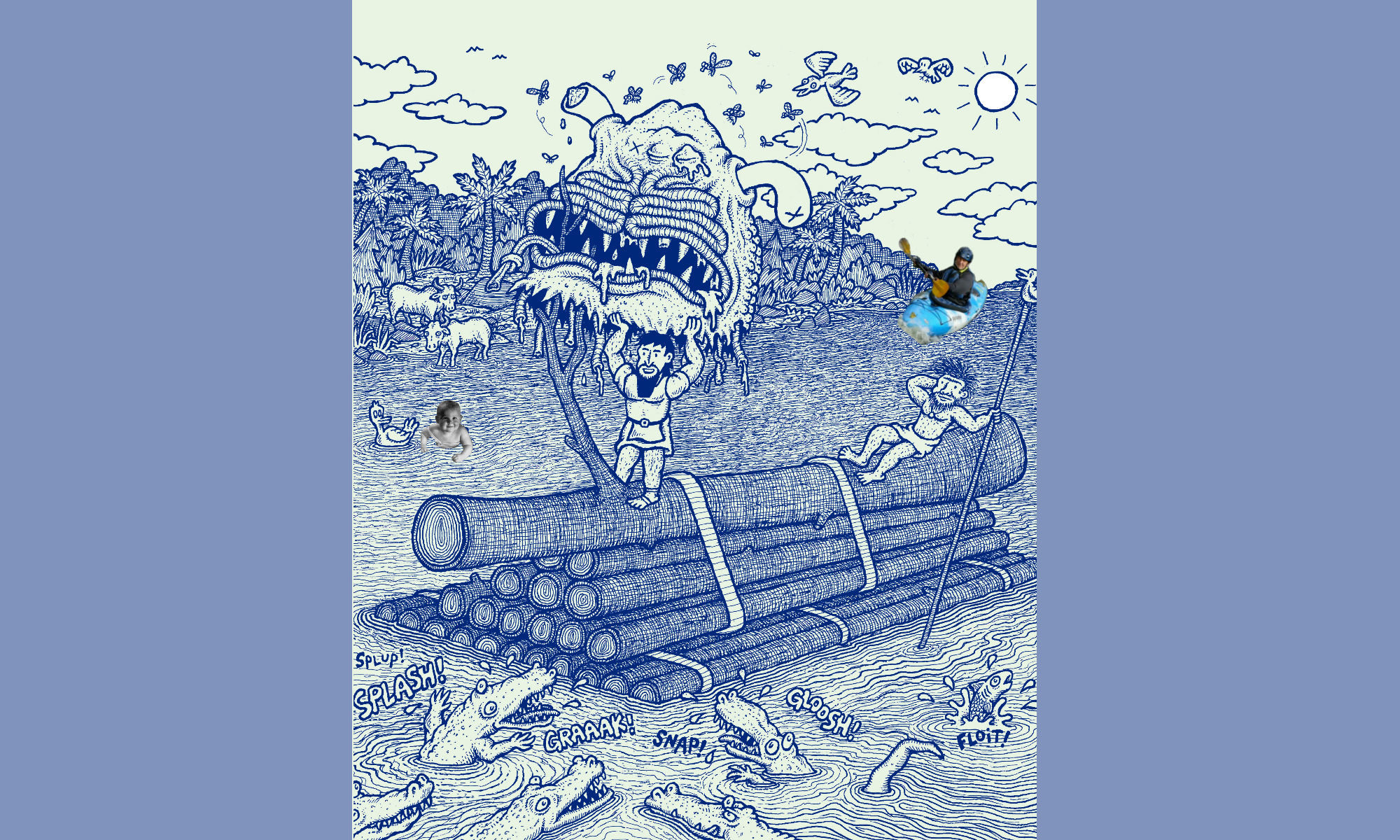

Reduced to formula: your polymorphous perverse male adolescent, sloughing off his mother and working out of his gynophobia, works his way to a homosocial love of chum, or even a huddle of chums, which love can only be consummated by an external act, the act ultimately but since no ready cultural wherewithal for that in 1958, given the attendant homophobia and that we really were just good old American boys, then the act must be metaphoric, and to insolate it further the focus must needs land on the other, some Other, any other. Gateway to gang rape, group whoring, queer bashing—sports is imbued with these tensions, is it not?—indeed, the whole spectrum of sociopathy from vandalism to tail-gating, gangbanging to villainies as yet undiscovered. Armies let loose, maybe, rape as a weapon of war, or just as a softening of prisoners—thumbs up! This yields the closed yet fluid triangle: shark, bait, and sharkwalker, circling around each other in an ever-descending spiral, ever-shifting roles.

You know, if he’d just once said Man, you’re crazier than I am, I might have retired content. After all, I finally worked out my patricidal attention-getting in other ways. But Reese never lent me the mantel. He couldn’t. What’s a performer without his audience? He needed his fans, and his bonny ideas man, and his bait, which was me, all of us, the live bait for his ravenous inner shark.

*

And the execution? He and I got as far as Atlanta, by bus, but no pistol could we find, just his dad's deer rifle; and busy selling Florida drivers' licenses (a box of which Reese had liberated from the Court House by vaulting over the counter when everyone's back was turned), and surviving one magnificent bar brawl (my one clear memory of it is of Reese, who I think started it, the arc of his empty pitcher crashing down on the top of one guy's head—so maybe we did kill someone), occupied with those adventures, we lost interest in premeditated assassination. I think Wells' reaction had something to do with my letting it slide, too; I have always worked on a long and subliminal (at least to me) delay.

And where does that leave us all today? I've lost touch with most of us. Wells is a top editor in Washington, D.C. Arty Loeb was stabbed to death in prison with a sharpened spoon, but Leopold, you may recall, was paroled after thirty some years, not without establishing prison libraries, schools, legal counsels, and I believe offering himself up for experimental drug testing. He taught himself Braille so he could teach a blind inmate to read, and too—I loved him for this little aside he makes in his autobiography—so he could read after the lights were out.

And who volunteers his time today to teach creative writing in the county jail, to the crack addicts? Who spent 48 hours in the jail as an inmate, known only to the Sheriff, ostensibly to write a story on it, which I only got around to writing four years later because I’d never digested the boredom sufficiently to understand why I’d done it, until this rag. Just making amends, doing penance, Lord, serving time. Harking back to complete a stage in my development that I somehow missed, namely prison.

Reese I've seen only a few times since we were grown. The tip of his nose is skewed, like a cap not screwed onto a tube quite straight. He wears his hair long and straight around the crown of a major bald spot, like Neal Young's—the Mandarin mustache, the aging Hippy look. He worked in Miami Beach for years (at the hospital we were both born in) as a lab technician, doubtless acquiring all the syringes anyone could want, and who knows what else. He and Kurt got into drugs in a big way in the late '60s, bales of marijuana floating in to them off old South Beach (before its transformation), swimming out to fetch them.

Reese had his house raided, was strip-searched in front of his artist wife and her two daughters, or maybe all of them were (she was a striking model), and all her bags of Plaster of Paris confiscated. What went into the evidence room mere Plaster of Paris, however, would come out cocaine, his lawyer assured him, and upped his bill and went to work, and got them off on some technicality.

Department of small worlds: that lawyer was my student in ninth grade English and French, in my old prep school where I returned to teach for two years before graduate school. Mickey, you surely meet your obligation to defend the guilty. Not just guilty. I think Reese had grown very nasty, out-Reesed Kent even. He taught elementary school for a time, and told me once that sixth graders were the best lays he'd ever had. Was he shitting me? I prefer to think so, though I actually don't, though now he has a kid, though he didn’t then, and in his defense I'll say: I saw him lie a thousand times, but never to me, and I could always read his irony where others couldn’t, and, I almost believe all that. That's a complicated defense, isn't it.

I often think if I'd stayed in Miami, gone to Beach High or even Gables—we moved just south of Coral Gables around the middle of my prep school career—if I'd just maintained some kind of contact with Reese and Kurt and Sandy and the rest and not made a hundred fathers of all my teachers plus a good many of the characters in Western literature, then I could have, really should have, wound up not like Reese, who last heard was alive and well and tending marijuana crops somewhere in Marin County, but wound up more like Kurt who with Reese sometime in those late '60s got in over his head, big time, and was found assassinated gang-land style, hands tied behind his back to a chair, bullet in the back of his head, his genitals stuffed down his throat.

I don't just think it—I'm sure of it. Reese would have waltzed or at least weaved through, come out if not smelling precisely of roses then at least in one piece, and I like Kurt would have been tortured, maimed and killed. Sometimes even now with a clean slate for a couple or three decades, I seem to be waiting for "it." And I do fear it, a whatever; something will catch up with me. I feel, I guess, like a perpetual debtor. It makes me selectively fearful, periodically afraid of flying, say—profoundly afraid of heights, faintly queasy and favoring the back of whatever structure. Me, the pre-adolescent cat burglar.

Maybe I pay indirectly, the sins of the fathers.... One of my sons fell off a roof some years back, destroyed his heel, paratrooper's fracture they called it, "like cornflakes" they said of the X-ray, nearly killed himself, an athlete now lame, just having a beer with his girl and moving to a higher perch on a roof, foot hit some moss. Did I program him as a child with 'imaginary' bedtime stories of a boy climbing over neighborhood roofs?

I'm afraid of my old bugbear Drowning (Reese fished me out, unconscious and settling on the bottom, the one time I would have), or really any loss of control, like being mugged, or just being punched in the face; afraid of growing feeble as a part of growing old, and being shouldered off the sidewalk by young punks (at least we were polite); afraid for my children, indeed for all the children between 18 and 21 that I now teach.

One of them in my office last week (wild man Hunter Thompson in the background again), recounting his travels in Central America, and how easy it would be to fill a backpack with cocaine and march across some border, etc.—a good cool million's worth. I told him about Kurt. I leaned forward and drove my most unflinching stare into his eyes and said, Let's open a window on my old pal Kurt, ok?

Do you think they cut his balls off before or after they shot him? Do they take the pecker with it? How many men to hold him down, pull the legs apart? How long do you suppose one has between knowing they're going to do it and their actually doing it? Think of the nicety of their balancing the shock you're going into from the blood loss, timing that against the final bullet. That must take a certain skill, a medical eye. I guess they get a lot of practice.

He was squirming and waving me off, but I kept on, mild and thoughtful in manner, utterly vicious in content, as vivid as I knew how. Don't mess around with dope when you're down there this summer, I said as he was leaving. I couldn't bear to think of you this way.

And when he was gone, I cried; I wept for him, me, Kurt, youth, time, mores, but, curiously, still mysteriously, not for Reese.