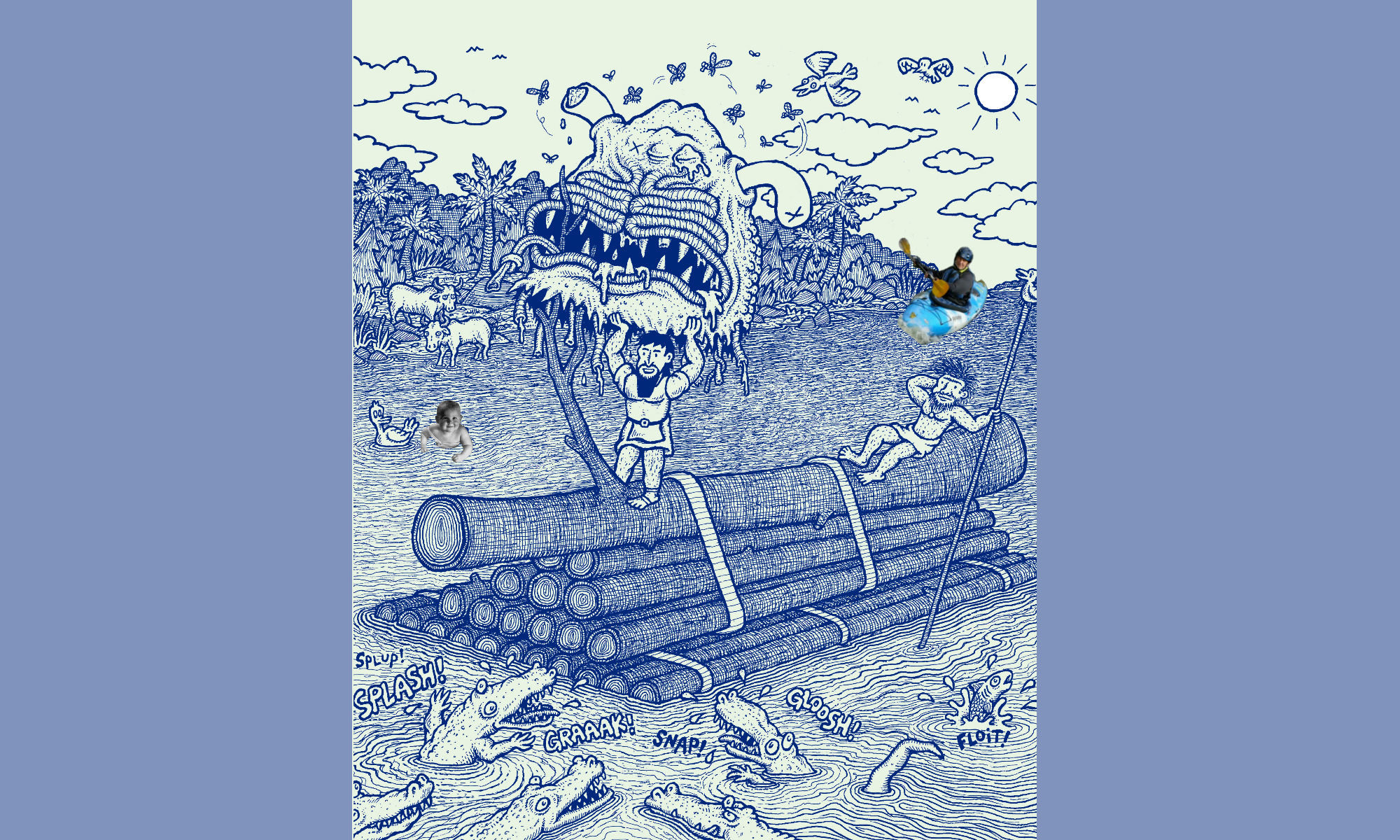

Obsession: [X] Kayak

By Kent H. Dixon

Bite your jacket.

~~A reminder to make your head the last thing into the confines of your cockpit, when coming up from a roll.

I love the double S-curved driveway behind my office building because I take it at 20 mph, shifting my hips and nudging gravity, pretending I’m in my kayak. Some large parking area—me crossing some lanes or blithely ignoring them . . . behold, it’s a boat! Everyone with the freedom and skills they possess behind a wheel—but I’m the only one that knows we’ve transposed to a river and boats. You guys, all you landlubbers in motorcars, would love being on some gravity-driven parking-lot—“America’s fastest growing sport.”

I love the very idea of it—me at age 70 pulling off this shit.

Kayaking is creeping into my analogies in class, as are rivers. It’s no coincidence we read Deliverance in my English 101 class. Dickey’s descriptions of the river and its feel are so good that I have to put the book down, go over to the gym and drag out the little Jackson I’ve got stowed in the pool storage room. Whence I go rolling in the deep end. I’m approaching a ‘bombproof’ roll—in a pool at least. Bombproof = able to roll under any conditions, even if bombs were falling. I love showing off, too. I get compliments, questions, while I’m just, you know, ho hum, going about my business, yes indeedy, a little rolling practice between classes.

When I’m in the man-made waves in the rapids they’ve constructed in my hometown in Springfield, Ohio, however, and there’s the frothing turbulent standing wave that wants to wash its mouth out with you, and the racing current and crazy eddy lines and it’s as cold as ice water and so tea-brown dark you can barely see your paddle up there above you once you’ve flipped, and I know—upside down under water, all kayak from the waist down, like a tethered Centaur—know the next hydraulic jump is coming soon . . . Not quite as good a roller then. No ten out of ten. More like five. Four.

I’m working on this. But it goes to show how delicate an operation rolling a kayak is: if you’re just a little off, dig too deep, lift your head too soon (“Bite your jacket!”), or worry about downstream and try to hurry and muscle your way through, you’re going to be “carping.” (Your head lifts out, you gasp a breath, and, oops, back under you go: like a carp eating the air.)

I love writing about this. Want the words to sweep by as fast and smooth as the rocks and sunken trees you see too late to do much about and comes now a 100 pounds of wave you have somehow aligned yourself to capture perfectly in your face (1 cubic foot of water = 62.4 pounds) and there goes that pair of sunglasses but it’s a power mouthwash and the breeze burns and the sun warms quickly and let’s get our butts to an eddy where we can rest.

Whew! And pew:

I love the rank earthy smell of rivers, even though the chill is like fear. Still, give me that imponderable mass of water hissing along endlessly different, endlessly the same, which, alas, I’m getting such a late start in learning to second guess. Give me 400 square miles of Biscayne Bay, in Miami. I understood enough of that massive body of water by the time I was 12—the tides and currents, shifting shallows, changing channels; its familiar fish and birds, I knew their habits and how to read the wind, the sky—the future of an afternoon: big as it was, the bay was home. But I confess these rivers baffle me. Guess I just got to get out there more.

I love the passing scenery, like an kinescope, the river banks sometimes downright industrial as you slide past a factory, some defunct and abandoned but some still churning away, churning out their whatever (often as not right into the river!); but other times, same river, you get something out of Heart of Darkness.

I also have to chortle when I paddle by one of the several Sewer Outfalls that empty into our creek. A sign reads: “Storms will elevate bacteria levels in the stream. Avoid contact with water.” And it gives you a phone number should you want to call Collection System Outfall #38. To ask them what? But I’m tempted: it would be like dialing up my past. Biscayne Bay, even in the 1950s,when I was a kid in Miami, on some days low tide really smelled like shit.

I love that my stroke is improving every time I go out. I love emulating Josh when I paddle—the main instructor at the kayak place where I go for various lessons. I picked up my new boat there today—a nifty blue splattered-with-white Pyranha Fusion—tentatively christened “Baby Blue.” Took me over a year to squirrel away enough cash for it. The hobby is not cheap, but I even love the hidden and not inconsiderable costs of supporting it. They’re mounting up, I’m not inclined to tally them, but I file away the receipts anyway. For a rainy mea culpa, I guess.

All that gear at the shop—the newest apparel, the endless designs of new boats, specific to every watery occasion there must be and then some. You never step into the same river twice, says Heraclitus. That’s for sure; rivers are ever new! Can change in a day. ‘Wasn’t there a hole here last season?’

Answer: Yup. —What happened to it? —Water covers rock, I guess. (And hauls it away, that particular rock having been about the size of a small SUV.)

Love the herons which everyone immediately remarks on how like pterodactyls they look as they veer down close to deliver a warning squawk. The ducks and woodchucks, carp and bass. Shopping carts and tires. You want a man’s job: try hauling a shopping cart out of the muck by yourself. You can’t do it from the boat. You need a pulley and a tree.

I don’t have a pulley yet, but did I mention all the stuff? I love my gloves and my boots and my PFD and the knife I bought to snap into it, which I doubt I’ll ever have occasion to use, but it’s so cool to have a quick knife handily fastened onto your chest. And the molded grip on the paddle—or the singing paddle itself!—Prince Valiant-like, the pressures it gives back, its little tingly messages to your fingers on the shaft that you’re doing it right, the gurgles and tugs out there on the blade, against the larger gurgles and tugs all around, gaining on you, yes, I even love the exhilaration I feel when those gurgles change up—the whole ‘room tone’ shifts a chromatic half-step like Space Invaders and you know, oh oh, here comes something white and nasty around the bend. That white noise that comes with the white water. Fear meets expectation meets just-as-soon-not-be-here meets put on your quick-reflex cap, pal, ‘And it’s all over now, Baby Blue.’

No one knows what that song is about—Dylan is saying good-bye in 1965 to Joan Baez? or to acoustic guitar? or David Blue or someone else, but come on, just listen to the words:

The highway is for gamblers, better use your sense.

Take what you have gathered from coincidence.

This sky, too, is folding under you

And it's all over now, Baby Blue.

You telling me that’s not about kayaking?

Speaking of the blue, white and nasty, here is a charmed segment of human time: it’s that moment where a group of paddlers gather, just above some kind of rapids—at the head of a boulder garden or some significant drop that you can just see the froth of—everything stalls as the kayakers pause and back-paddle to assess what’s ahead and figure out the best place to take it on. It feels something like a team mentality, all of you paused there, jockeying, shouting above the roar:

—River right, easiest. —Yeah, except for that strainer at the end of it. —How about this mother right in front of us? Take the green finger, push by the rock to the right and then bank on that reaction wave curling over from the left.

Jesus, that wave looking to me like a surfer’s barrel somewhere off a Hawaiian coast. Paddlers hardly ever go the same way, I figure, because you can so easily get pushed off your line. When I was a rank beginner, I’d just hang back a little, wait to see who handled it best and then try to do exactly what they’d done. But that rarely seemed to work, and half the time you find out later they chose that way for the bigger thrill, or, even more amusing, they knew even less about how to read it than you.

So you learn to read the river and the rocks, the eddy lines, the upstream V’s and the down; the holes and the pillows and the rooster tails; the tongues, the haystacks, the boils (like someone is percolating something under there), ah, this fluid femme fatale: lolling and stretching away from you in the sun, her ripples like cellulite, her meander like storytelling.

Meanwhile, the books and DVDs keep showing up in my mailbox. My corner in the basement where all this stuff is mounting up: a dragon’s lair with its hoard of gold —knife, whistle, dry bags, ice bag, chemical ice; bungee cords and safety throw-rope; paddles, spray skirt, dry skirt, shirts, helmet, pants, PFD (Personal Flotation Device)—why it’s not called simply a life jacket is still a mystery to me, but then, I’m a novice; I’m an eager beaver, I’m probably a joke. I’m insufferable, I’m sure. Man, I got so much to learn, and so little time. In ten years, won’t I be too old for this? Hurry then, because I do loves it so!

It cannot be said that it’s a perfect love, however. In fact, the non-love can be so altogether gripping that I sometimes wonder if I really love any of it. Would like to be rid of it, wish I’d never taken up this extreme sport, and am secretly relieved when we have to cancel some days. One wonders: why do this to oneself? And then the larger question: obsessions per se, like all those lonely people, where do they all come from?

Mine may go back to drowning. I drowned once in Miami, on a bet when I was seventeen and we’d been drinking beer all day and I offered to swim four lengths of Mary’s pool under water—maybe 50 yards total, maybe 60.

I put up $20, each of them put up $20, and off I went, emboldened on Bud. I passed out on the last leg, glided in. They tell me I bumped my head on the end, rolled over and let forth a cloud of bubbles, from three feet down. They thought I was showing off, mocking them with air to spare, and walked away from the pool.

But Grant said, Something not right, and walked back. Emphasis on the w a l k i n g there, for I was on the bottom turning an awful blue-green—and he said my eyes were open and oddly expressive, a kind of helpless farewell.

Meanwhile, I was having the “tunnel experience”—of light, with music—from where I lay I could just see the ankles and bare feet of the choir on the bleachers, they were in black and red robes singing the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah (this was years before I knew Handel from a handsaw), and the light was so gushy wonderful, so very very somatic, a lavage of dopamine I suppose, that when I came to, to Grant leaning over me about to give mouth-to-mouth respiration, I slugged him. God damnit, he’d spooked my vision!

He slugged me back.

They didn’t pay up, on grounds that I hadn’t really won: drowning hadn’t been part of the bet.

Today . . . when I swim . . . probably every other time I go to the pool, I try for a length and a half underwater. I want to be able to get out of an airplane that goes into the drink, or a ferry somewhere that tips over. Ecstasy (the endorphins) aside, I really, really don’t want to drown. So, upshot is, for an old fart I can hold my breath a long time. So long that if my roll isn’t working and I do have to wet exit around instructors, I actually do it sooner rather than later in consideration of them, so they don’t panic.

So to say, drowning is a complicated issue for me. I fear it, train against it, and would seem to test it, but all that said, I think that beating it is just a small part of this obsession with kayaking, or rather, with its downside—my inordinate dread.

What’s really behind it, then, the big cathected kahoona?

Long story. In short, and somewhat sappy, I think my parents neglected me. They were party animals, post-World War II in Miami Beach, where the 7th Fleet had been stationed and the parties were solid state and just because the war had ended and the 1950s rolled around, that was no reason for anyone to put up their cakes and ale. I remember police arriving at our larger parties, responding to neighborhood noise complaints, and before you knew it they were walking around in shirt sleeves carrying their own drinks, letting me handle their guns. Hey, mom, what can I say? This is what I remember.

So I think I sort of got farmed out. When they went off on cruises, to the Bahamas, the West Indies, they’d park me in boarding school. Three months once, right through Christmas. Fifth grade. I didn’t know better at the time, but I came to realize it as an adult and actually resent it, less adultly, in my fifties. But certainly I was reacting unconsciously back in my teens, when I would have been better off with the three months spent in Reform School.

Plus, my family dynamic was totally sick: my father, my family, lived off an allowance from his mother. Dad never really had a job, so we were always kowtowing to my grandmother, less she withhold the rent, or not pay the Liquor Store bill, which was considerable. We tip-toed around her vainglorious whims. When the stock market took a swan dive, she would rent our house out, and we then lived in some virtual projects, though I still went to Miami Country Day School.

I learned to flatter, not confront. Ignore. Lie. Pretend. “Your father’s job is your grandmother,” mom said. Well, it made sense—I liked my private school, my wealthy friends, my Sunset Island (the house today is valued at eight to ten million; grandmother Rosalie bought it for them in 1940 for $15,000). I had my own speed boat at thirteen and water skied to school.

But jump back a few years, when I was nine and ten. They wanted me to be a sailor, like them—my mom won ladies’ regattas in Snipes and Sunfish, and my father crewed for an Olympic bronze medalist to win the Miami-Havana Yacht Club race two years in a row. But I couldn’t stand the stupid little boats they tried to push off on a select group of us kids, 8 foot prams—a sailing dinghy in effect—so they finally gave up and got me a 3-horse power British outboard motor for it, gaily wrapped at Christmas with ribbon and a big note that said, From Santa to Stinkpot.

Oh, god—freedom! I escaped those convivial lunatics daily, soon as I got home from school, and every weekend, for years. For three or four years I’d take that tiny boat out into Biscayne Bay, when I was nine. Ten. Eleven.

Now Biscayne Bay is no Golden Pond. It’s gigantic, some 450 or so square miles from tip to tip, 35 miles long, 8 or 10 at its widest, with all sorts of shallows and tides and uninhabited islands—and disappearing islands! a storm would efface them, and then over the next few months some semblance of them would reform—and causeways and currents and boat traffic and porpoise and sting rays and ospreys and manatees and pelicans . . . I guess I should want to have my ashes sprinkled there, it was such a huge part of my childhood, but I never felt the water was my best friend. That bay could gang up on you fast. Twice I was swept out through Government Cut into the shipping lanes and, I guess, the Gulf Stream. Hey, meet me in Cape Hatteras. Me and my eight foot pram. My little 3-horse power wasn’t always up to the channel currents, especially if I mistimed the tide. Once the Coast Guard towed me back in; another time a pleasure boat spilling over with bikinied bathing beauties, and everyone on board was so drunk it was more dangerous to stay tethered to them; they were going so fast it was dragging my bow under, so I unbelayed and I’m sure they never noticed.

I got caught in a storm once so violent that I could tell it was going to flip me over, and I’d be out there with a swamped boat, drowned engine, unable to see over the waves. So I slipped over the side and clutched the gunwale, and rode it out. It worked, I’m here to tell you about it . . . MOM! What the fuck were you thinking?!? If the earth had been flat back then, I’d have sailed right on over the edge any number of times. Was that the secret plan, save on babysitting?

These be the inner child’s recalls that my mother’s two year cancer decline activated in me. Where the fuck were you, why should I do all this now—change your dressing, irrigate the drainage tube, manage those finances, drive you to chemo, help you to the shower, fix your nocturnal martini the way you liked it. I got past the resentment, but it took some doing. And, don’t get me wrong: I loved the girl, too. A lot. She was pretty, and tough—chosen first or second, or before me at least, when the neighborhood kids played backyard football—and a whole lot of fun, life of every party I ever saw her at. Even when she was mad at me, we could get the giggles. But I just think she, they (mostly she, dad was sort of useless as a parent), were a bit . . . oblivious? Nonchalant? Guilty of criminal neglect? Secretly wanted to be rid of me? The reader may be able to tell: it still pisses me off to think about it. And if I think too long, it makes me sad. Oh . . . deliciously sad I suppose, because, I must say, it gave me almost unlimited freedom, and I still wouldn’t trade that. So.

So I’m digging around with my therapist for the whys of my kayaking obsession, and he reminds me of my pram and all the castle intrigue I navigated through, the narcissistic grandmother, the alcoholic father, the masks and the mendacity, the co-dependency and the cunning—just to survive. Therapist and I call this my Br’er Rabbit personage. Jus’ don’ throw me in the briar patch, massah. I was either outwitting or outright lying to some adult, or even some contemporary, day and night. I didn’t really know it wasn’t normal, I doubt I even knew the difference.

My therapist reminds me of the neglect I was escaping and all the attendant escape mechanisms—the sneaking out of the house, the filching of all that money from purses and wallets (once blaming it on the Exterminator—poor guy got fired), and the setting out in my little boat, to face that gargantuan bay, which drew me like a warrior’s heaven, but scared me like it, too—Valhalla’s for dead warriors after all. I can remember feeling a special dread as I readied the boat to launch, and I discover this is the same dread I feel all morning when I’ve got an afternoon kayaking date. It goes away about half an hour before putting in, when I think the adrenalin takes over. But I think my pram was the same way: to set out under that concrete bridge by our house, its echoing arches, the eerie amber dancing ripples reflected on its low ceiling, was a kind of through-the-looking-glass passage, but I seem to recall being up tight about it all morning, checking the equipment, extra cotter pin, pliers, gas line, spark plug. Is the choke clean, starter cord not too frayed, enough anchor rope, what time is high tide today, where the heck did Dad put that floppy plastic cooler?

Jim, I say to my therapist, For that much anxiety, why am I always making dates to go out on the river, feeling this dread even when it’s the placid Reservoir. He actually laughed. It was so simple: You’re just reliving the trauma, he said.

He lines up my Biscayne Bay, and everything it was an escape from, how fraught my life was with contradiction and denial and connivance, lines it up with my Buck Creek and Mad River and says the one is the other. Forgive me, he says, but they flow into each other.

Well, ok, sounds reasonable; granting him that, I popped him the next question: If I relive it enough, won’t it go away, won’t I “spend” my water world youth, get some control, come to terms with parental neglect and settle down in retirement and actually enjoy kayaking, instead of always experiencing this angsty, incipient dread about it?

And he smiles and shakes his head and says, No, it doesn’t work that way.

Any experts out there? Anyone care to say why reliving some trauma or other, however complex, however diffuse, doesn’t sap its energy, doesn’t loosen its hold on you?

Because you have to process it. “Write about it, talk about it, till you’re blue in the face,” he says. Just reliving it more or less stokes its engines; if you want to deplete it, you analyze. Unpacking Biscayne Bay, I could call this.

“Did you tell Mimi about your Google experience?” he asks.

No, she’s tired of hearing it. I can’t even mention kayaks, much less my stupid little pram. My wife’s had it with my past.

Gotta tell her, he says. It was very vivid when you told me.

Earlier that same session I’d told him as how I’d Googled Biscayne Bay, to see if I’d forgotten anything for my essay (who knew it was 35 miles long, for instance!). And I’d googled through various concatenations all the way to the north bay, where I never went as a lad because it was so far—I was central and south bay (and the Florida Keys if I weren’t careful). And clicking around through the lore of the north bay, north of Baker’s Haulover and Bal Harbor, up into Indian territory—tributaries, estuaries and hammocks; a strangulation of mangrove and shark-like cobia and razor-toothed barracuda and—can this be?—the last North American crocodiles . . . ?!

I began to feel sick. That is just too much to heap onto the plate of a ten year old, 20 miles from home, at sea with a 3-horse power outboard clamped onto an 8 foot boat. Feel sick and helpless. It’s that same soft rotten spot in the pit of the stomach, whether I’m 10 and putting around the barnacled seawall with my gig at the ready looking for crawfish and being startled by a leopard ray; or whether I’m 70, paused at the staging area above a four foot drop and wondering how to ‘bank’ on that giant serpent’s tongue of a wave, either way, I felt and I feel an enervating nausea that I want to run from; I felt, in that googleplex of dangers and hazards of the north end of the bay, where you could be eaten alive by fish or fen alike, felt like I’d walked up to the brink of an abyss and I just wasn’t going to peer over it, look down into it. I mean, predator fish aside, what to do about the Maisy Bird parents and scurrying after stinted love?

I got out of Google. I walked away. Folks, when you’re frightened by Google, you know you’ve got something really big and nasty, and primal, by the tail.

Does that help, Jim? I’m a little weak right now just reliving that virtual computer moment.

Don’t forget the detail, he says. Oh, yeah. He told me that when one does process these trauma, one should include the most insignificant detail. I forget how this works, for processing; I’ll get back to you on that. But we all know it works for poets and writers: “Learn the love of inconsiderate things,” says Rilke. “Be one on whom nothing is lost,” says Henry James.

At a subsequent session I went back to the small change. What’s the mechanism, I asked him. Why is the devil in the details?

“Because you’re normalizing the abnormal,” he said. Step by step, detail by detail you take apart the monster, the unknown the scary the denied the unbearable-to-look-at. You can really do this only by cutting it down to size, a piece at a time.

I sat there wondering about obsessions, on an evolutionary scale for instance. Their purpose, their reason for being. What about ‘good’ obsessions—the only way you get some things done. What about recapping some expansive joy, I asked him. What if I want to revisit it forever? And what about sexual fantasies? They give you your edge (a kayak term). You don’t really want to spend those, do you.

“Well, then, you don’t,” he said. “Do you.”

“Do I what?”

“Well, what about Mimi?”

Wait a minute. This is going into an essay.

“No, I mean, what about your boat on order, and Mimi?”

“The boat came,” I said. “It’s in the boathouse.”

“And does she know yet?”

Well, reader, she doesn’t. All my friends do, my students, strangers I stop on the street like the Ancient Mariner that stoppeth one of three, but not my wife. On the surface, it’s a money issue, and an obsession issue. Wait a year, see if it isn’t one more of your galloping hobbyhorses, she said. It’s been two, and the money’s mine, saved all $900 of it from my discretionary fund (as we move into retirement), and even my therapist, giving me a little leeway, once said that’s less than what a decent bag of clubs costs. So is there some reason I haven’t told her yet, some wherefore I’m hiding this new boat in the school’s boathouse, in the middle of winter, bothering almost everyone I know with the news and the fact that it’s sub rosa (to her), just waiting for a reasonable day to take my Baby Blue (or Blue Meanie—which do you think?), take her out on her maiden voyage?

Me and therapist look at each other, knowing what he’s going to say next:

“Br’er Rabbit,” he says, beating me to it.

And nailing me to my cross, really. More than one way to keep the palace intrigue alive and sneaky, I guess, and how clever of me to bundle a couple of trauma together—the perilous bay and the dubious parenting, sealed into a nine foot kayak with a retractable skeg.

Ok, back to unpacking; here’s a kayak detail: I love pushing off, maybe because it’s one of things I’m good at: you’re on a river bank or the edge of a pool, and you launch yourself with paddle vertical in the right hand, left hand over the other side, and push off with your arms and a scootch of your hips. We have a little run near the boathouse where you can do this from the top of the road, and plunge down the fifteen foot embankment over the wet grass right on out into the river, right on out into watery bliss, too, with your body in your hull set to make really great medicine with the infinite contours of the river.

But for the bay, here’s a trickier particular. When the bay was calm and the water was clear, I adored peering down at the bottom. Fascinating! I’d kill my motor and just drift, stretched out on my stomach to peer over the bow, so as to sneak up on the fish. I wanted to install a glass bottom window in the bottom of my pram, but dad never got around to it. Was afraid it would leak maybe. (Ha!) The crustaceans cruising through the sinewy reeds, fish darting away, that whole other greeny-grey, ruddy-pruney slightly magnified world down there. Or even just the sinusoidal ripples in the sand, me a fractal aficionado two decades before Mandelbrot got into iteration. I studied these grooves, extrapolated to speculate on the tides and the wind and the waves. Such pleasure, to feel in on nature’s secrets, or figure them out in spite of her, or even just attempt to.

But maybe it’s just as well dad never got around to that glass-bottom peep hole. What if mom’s face had shown up framed in it, pearls of silver bubbles streaming out the nose, mouthing silently . . . what? Apologizing? Wondering where the hell was I and get home this instant? Or maybe, probably, just wanting me to fetch her another vodka martini from the bar. Even at the end of her life, when she’d shrunk down and gotten so frail and boney it was tricky just to lift her, even in those final days, that evening martini was de rigueur.

Thing is, were she still alive, and maybe just a little younger [she did go white water rafting with me and three of her grandsons in her seventies], I think she’d go out on the water with me. I can see her running one of those pools in the park, driving herself to compete with me. What an afternoon we’d have drifting along, reminiscing over the watery couple of decades of my youth together, and you know what? I guess I just wouldn’t even mention the bay.