LORELEI

Miami, 1950

He hated sailing in the stupid little präams built for children, a fleet of flat-bottomed, gaff-rigged sailboats each about the size of a bathtub, with a name sounding like a baby carriage. In fact, he hated all sailing, and worst of all was sailing in the ocean with his parents, though that wasn’t a question of nine year old pride.

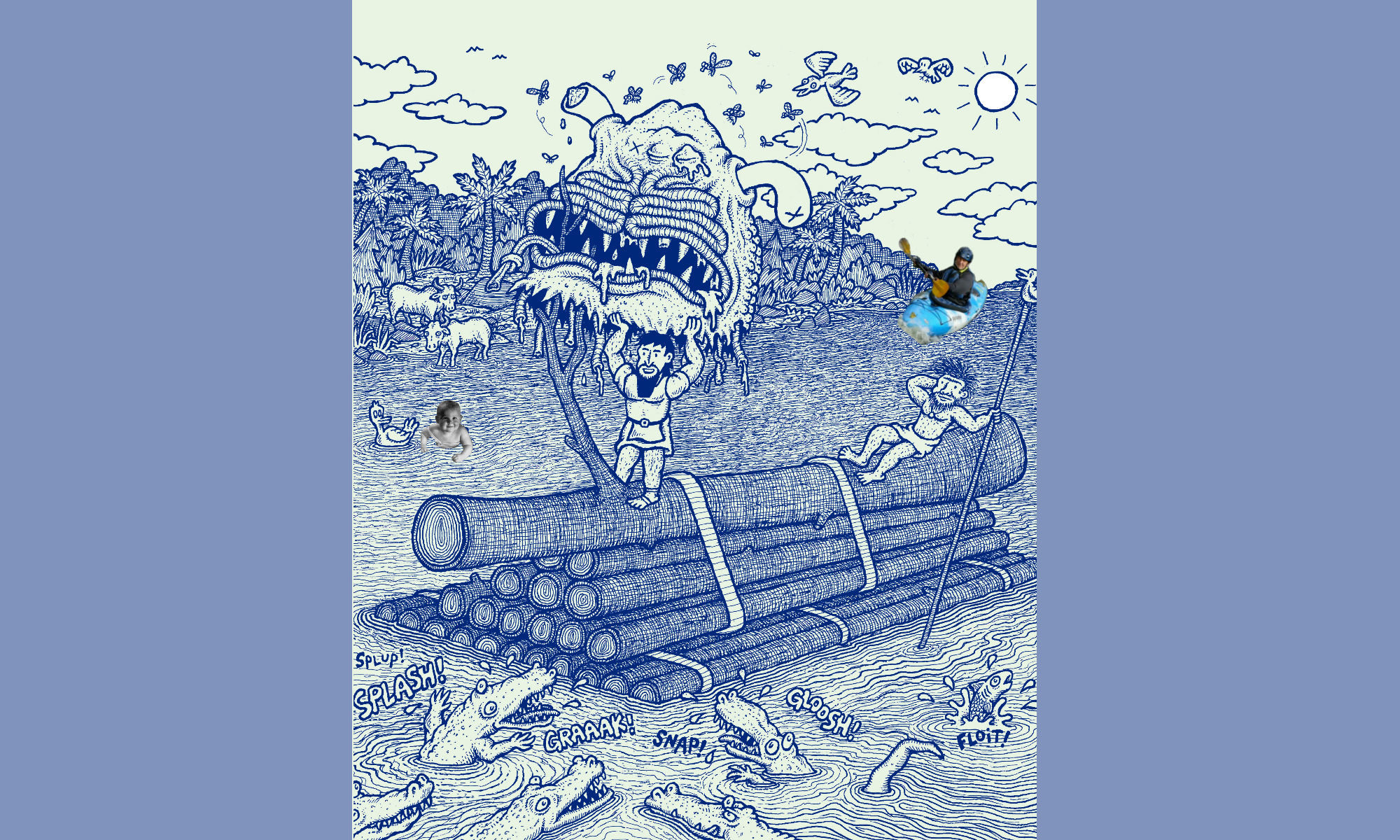

It wasn’t that he was afraid either, at least not of drowning. He could hold his breath close to a minute. He was a water-baby, they said, swam before he walked. Once their boat had capsized in a squall, trapping him under the sail, but the waves, sucking the sail down like pudding stuck to the bottom of a spoon, had merely taken turns letting him breathe, and what light had streamed through exposed the clutter under there with him, especially the hats eddying around as if people were swimming under water, which had made him laugh.

He had studied it while waiting to be rescued: the angry scribble of lines pierced by one taught steel halyard that shone like a scratch across a photograph; this and the debris were what kept bumping into him and not some brazen fish nosing around, big enough to swallow them all. He’d seen these fish, huge tarpon, casual as tigers—sometimes it seemed the whole speckled bottom had decided to pick up and lazily move out from under.

So he feared and hated sailing for the risk—the fish it tempted, with him—and he simply refused to go; and when he was eight they gave up and bought him a three horsepower outboard for his pram and called him a stinkpot, some pride in that. But when he was nine he discovered remorse: he hadn’t been with them the day they spotted Lorelei.

An arm had actually waved, his mother told him, a couple of hundred yards off; it could have been a porpoise breaking the surface, or a palm frond waterlogged, upending to sound out there in the jittering horizon. Maybe it looked like that, but it must have also been as if she were waving, calling for help.

They’d come about, re-tacked as fast as the bay’s afternoon doldrums would allow, back to where they’d seen this mote in the sun’s level eye, no doubt chunking the cork-handled church key into the last can of beer as they speculated, probably joking but with a slight catch in the throats too because whatever it was that had come up to wave had gone back down when they got there—maybe just a sting ray, the tip of its fin curling like a human hand. But something had thunked against the hull and they’d all peered over the leeward side at the plaster store mannequin floating face up, wide-eyed and wholly pink, naked, a few inches below the surface. A modular female, chipped in places and thoroughly pocked on one thigh—probably hit by a school of mullet, his father said. Probably why she got fired, his uncle said. You can’t work at Burdine’s and run with mullet.

She was disturbingly bald and would twist apart at the middle if you weren’t careful, but she had both arms and jointed legs, and red lips that seemed about to part right at the second of having thought better of it. His parents brought her home, dried her out, touched up her scrapes with putty and make-up, and his father actually painted nipples on her and penciled in a belly button.

They named her Lorelei, a kind of German mermaid his mother told him, that lured sailors to smash their boats on the rocks. Why couldn’t they drop anchor off shore a little and swim over, David had the sense not to ask. Never let them know how many questions you had, was a first rule: they might take your freedom away. Besides, he could usually figure it out himself. Maybe German sailors were afraid of fish, too. His uncle had spotted a German U-boat off the Miami coast during the war. An official sighting, north end of Miami Beach, about 85th Street.

She combed her hair with a golden comb, his mother said, and from a mop they fashioned their Lorelei a wig, which made her look silly. David preferred her bald, though he liked the eyelashes she’d sprouted one morning when he’d lifted her off her face from among the ashtrays and watery drinks scattered around the floor, his parents till asleep upstairs. Now she had a penciled tattoo about Kilroy on her fanny, peering out of the crack. Kilroy was somebody who’d gotten around a lot in the war. David rubbed it off with spit and a cocktail napkin. It left a smudge, like a bruise.

He was faintly jealous. Though she was a kind of sister, she was older and moved entirely in their world, sat up late at their parties until she toppled over from neglect, to appear startlingly all over the house—at the kitchen table the next morning with a cup of coffee and an ice pack on her head, or on the john with a Life magazine on her lap, or in the bathtub on all fours wearing a bandanna and an apron, a hint from one of them to the other to clean it, the latest live-in maid having given notice when she woke one morning to find Lorelei sitting on the end of her bed wearing only an apron, heels, and a nurse’s cap. But David and Lorelei managed to steal a little time together, too.

The first time she danced for him he’d been in the den turning the dial between his Sunday radio specials, “Boston Blackie,” “Nick Carter, Private Eye,” and “The Shadow.” Hmm mmh mmh hmm ahh hahahaHAHaHA HA HA…and he’d inadvertently tuned in a music station. Lorelei was sitting behind the desk wearing his father’s reading glasses and the Hawaiian shirt that had become her housedress, and he could see under the desk from his position on the floor in front of the radio, her bare feet, with the toenail polish defining the fused toes, which recalled a time when he was five and his mother’s friend, Blainey, had danced, not so much for him as to him. At him.

His mother out, everybody out, David left alone with Blainey, who was drinking and playing victrola records and dancing; without a word she’d put down her glass and set little Davie Francis up on the big puff pillows on the couch and danced barefoot, twisting on a heel-toe step and twirling her hair, and then waving her arms in a hoochy-koochy sort of hula, embarrassing him the way she rode the music with her arms and hair, and twisted and dipped and kept swinging and flowing and spilling it all right at him. Maybe he was six. He hadn’t known whether to pretend he didn’t notice or what.

So now he went to her and removed her glasses and mop, slipped off the shirt, and helped her out of the desk chair. And made her dance, like his toy soldiers: he moved them, he spoke for them, sounded their rifles and ricochets, yet could lose himself completely in their spying and skulking and the many dangerous predicaments they got themselves into, all on their own. If they were wounded, they might well die. For that battle anyway. If Lorelei wanted him to take his shirt off—she was older, he’d best comply. She didn’t insist on his pants.

She lay on the floor and waved her arms and legs like a god he’d seen in an Aladdin and the Lamp movie. Then with her arms sticking straight out behind him, her hard belly to his face, she danced out the one song and on through the announcer into the next one. She sat on the couch with him and put her own hand on him where he put his on her, on her chest and insufficient ears and shiny cranium, smooth yet dented, like a ladle. He touched her eyes. They touched their fannies together. They fell asleep on the couch, and he fairly threw her across the desk into a heap on the chair when he heard his parents’ car pull into the garage.

Hi, Dad. Look, Lorelei fell over. I was just . . .

His father helped him set her up again, and draped the shirt across her chest and tucked under her arms the way mothers wear a towel out of the shower. The next day she was put in the closet: it seemed a kind of punishment but he didn’t think about it. That same week she fell out of the closet onto his grandmother, scaring and almost hurting her; so that Sunday night Lorelei was set out front in a rusty and tattered lawn chair to be picked up early Monday morning with the trash.

The garbage men didn’t even take the chair; they merely crossed her leg over her knee—as if sitting all night she’d finally shifted—and gave her a ratty sun hat and drove off leaving her to preside over the emptied cans now lying on their sides.

His father hung a For Sale sign around her neck; his mother said that would be misunderstood and made him put her in the garage, but it was too busy for her there—the tools, the work bench, the boat he’d been caulking for months. She got in the way. He didn’t like her backseat driving, he said. So before next pick-up he’d taken her apart and wrapped her up in newspaper—a pyramid of bundled torso, limbs, chest and head, out by the street at the end of the driveway. The garbage men stuffed a folded note in her half-open mouth: “Break her up small we take her.”

Behind a far hedge his father stood over her parts lying bright pink and gestural on the grass, like a daddy-longlegs when you pulled its legs off and waited, after their wiggles stopped, for one more. He stood amidst these poised arms and legs and naked halves of abdomen, and prone head, hefting a sledge hammer at waist level. The boy waited; the father hefted, waited, then put down the hammer and fitted Lorelei back together, and dumped her in the hammock on his way back to the house.

Next day the police called: neighbors had complained that Mrs. Francis was nude sunbathing again. His mother, irate, marched out and put a bra and underpants on her, and a glass and pitcher on the wrought-iron table beside her. And sunglasses.

Gradually she left the hammock and began to lean against various trees deep in the backyard, away from the street, and finally, to protect her a little more from the rain, she was wedged in among the sturdy sucker roots of the giant rubber tree, the leafiest of them all, that cast its shade out over the canal so the bottom was clearly visible when all else was sun’s glare. It was like the viewing window on the floor of the glass-bottom boat at Cypress Gardens. When he wasn’t netting the stone crabs or spearing the crawfish with his three-pronged gig, David would lean out on a limb over the canal to watch them amble and bump and raise their claws to threaten (they looked like the jai-alai players with their long wicker rackets), and the crawfish would scoot-and-glide across the mossy rocks and scooch back into coral corners, all of them inside that magical verge of clear shadow. Sometimes, spying from his tree, David would wish—so hard he knew it was a real prayer and not like at bedtime with his grandmother coaching—Please, God, just once, can’t I watch my solders move around by themselves, like this?

It had been his tree since he could first climb. His imaginary friends, Concrete and Jonah, had lived in it until he’d more or less outgrown them, or at least stopped playing with them, or they with him. Concrete had been any ugly but nice giant, taller than the tree itself sometimes, with a head something like a turkey’s—he was so tall you couldn’t quite make it out, but there was the red grainy skin and especially the flaccid wattle. And Jonah, who did the talking, was about the size of Tom Thumb and wore the same kind of dungarees as Johnny Eddleston.

Now Lorelei stood at the base of their tree collecting bird droppings and growing slowly soggy; she was beginning to smell, in fact, after a hard rain, which greatly disturbed the bees. There were no holes in Lorelei, but she was rotting inside. The bees couldn’t locate that stuffy rotten sweetness of paper and glue and something sharper that made his nose balk, so they’d earnestly buzz around and then go looking in the tree, even among the upper branches, where the leaves were so thick they would close in below so you couldn’t see the ground.

He couldn’t easily see her either from his perch, but she was down there—her mop wig a crusty, caked mess now at her feet, her red lips pale and running at one corner down a weather crack in her chin, her nipples and navel and toenails and tattoos sun-bleached and all but washed away—looking out across the canal, a stony sentinel like a backyard statuette, but still evoking the occasional boat horn from a yacht motoring by, choosing the low tide so its poop could pass under the bridge. Clearance 8 Ft, the sign had read since he could read. No Wake.

Today he wished he’d brought a comic book. Having Lorelei at the bottom of his tree wrecked everything, like having friends over to play who didn’t get along.

“David?” she called. It startled him. He froze. The bees kept whipping around and pelting him but didn’t sting, and his mother called again and then stared out over the canal. She’d stand at his bedroom door like then when he was playing soldiers and he’d sit still—pretending to think, as if he hadn’t heard her—motionless above his motionless battlefield, until she left.

But now she didn’t leave. She walked slowly along the sea wall, pausing, peering down. For what? Even if she did see a stone crab she didn’t have her rubber gloves with her or even the net. She was the one to put her foot on their backs to twist their claw off, just the big one, and throw them back to grow another. A stone crab could snap a pencil clean in two with its main claw. She’d pull the crawfish off the gig prongs, too, and twist their tails off. He was proud of her. She was always chosen first, or second, in backyard football, though he didn’t always like them tackling her. Sometimes it even made him a little embarrassed. He felt sorry for them, too, to know he had the best one.

She walked onto the dock, knelt and stretched out flat on her stomach, gripped the edge to tuck her head over the side, looking underneath. From David’s crow’s nest she looked like Lorelei in shirt and shorts but without her head. She might have called him once more, her voice muted and echoing out from under the dock. He studied the sap oozing from the stems he’d snapped; on his skin it turned quickly from milky to sticky brown. He could write with it, invisible till it dried.

Soon his father was calling somewhere. She’d call “Da-vid . . .” and then he’d answer “DAVID!” “Daa…vid…” Their voices were closer in pitch than a man and a woman’s ought to be. He had to part the leaves now to see them, on the dock looking out over the water, but he couldn’t hear what they were saying. Lorelei was close enough to hear them, but she never told anyone’s secrets, not theirs, not his.

His father hugged his mother’s shoulders once and looked right up at the bottom of David’s sneaker, which he didn’t move but let his foot go dead, up to the knee, the whole leg as dull and apt as the tree limb, and his father looked and didn’t see him. They walked, his father and mother, back toward the house, his mother calling one more “Daaa…,” which broke off and then sounded as if she were laughing.

There was plenty to pass the time with, the changing light, and different noises: how the different waves of breezes wheedled through to rustle the dark leaves differently; the bees were never content with their hold on a leaf or stem that he’d snapped to let them nibble at the milky sap. Fidgety bees, tumbling like clowns, with the striped pants half way down their behinds.

Concrete? he asked. Jonah? Does Concrete still live here?

Though the branches became too thin for him to climb much higher, it seemed, in his leaf cocoon, that the tree was vast, with whole other hemispheres branching out, full tangled unexplored jungles of dangling, snaking sucker roots that he had yet to brush aside, and somewhere in them sat Concrete, smoking his pipe, waiting for Jonah to return on his dragonfly or something.

He tried hard to remember, when he used to talk with Concrete and Jonah, if he had talked out loud. And did they? How did it work when he’d been little? It wouldn’t work now, he knew, not with Lorelei down there.

He moved some branches to drop berries on her and that was the second time she danced for him: he heard her steps in the grass first, and then he saw her jerk, lean, throw her head back to look straight up at him, and then break in the middle—it was his father tearing away at the Ficus vines to free her. David dropped a berry anyway.

His father walked off carrying half a mannequin under each arm. Back toward the house. If he’d called then, David would have answered, but when he returned later, two men accompanied him; then others arrived in a boat, which did not tie up but idled and revved its engine to hold its position in the middle of the canal, so the men lined up on the seawall had to cup their hands and shout, keeping their distance from his mother sitting on the tackle box on the dock—he could just see her legs and the cigarette between her fingers resting on her thigh, unlit, like she was mad. That made the men afraid of her too, because she was mad. But at what?

More boats, two or maybe three, with the large motors on their decks he associated with dredging rigs. Much of Miami Beach, certainly the island they all stood on now, had been dredged up by such boats. But why run the thick ropes, with the huge pulleys, the fifty yards across the canal, maybe sixty, further than he could throw anyway and he’d been practicing for three years.

Something big was going on with all the diesel fumes and the yelling and chains clattering and lumber clunking on hollow decks, and he was going to miss it if he didn’t come down. And then, just as if he had, not jumped as usual but carefully stepped the last step to the ground and come out from behind the tree, he saw in his mind one of the men see him and say “There he is,” and all of them turn, and his mother . . .

They were looking for him, weren’t they. They were dragging the canal looking for his body. She thought he was drowned.

The frogman confirmed it, jumping over the side and then treading water, face mask up on his forehead, to talk to a man standing on the dock now beside his mother. There were pauses in the din, when all the sputtering exhaust pipes would dip together below the jumbled waves from the boats’ sluggish circlings, that were quiet enough to hear the man. “Yes, Ma’am,” he heard. “ . . . in our favor. If. . . missing since . . . Them currents . . .” and the man pointed.

David couldn’t see at what but knew he was pointing under the bridge. It took all his strength to paddle his praam out from under that bridge against the tide, the times he’d let if drift under there to surprise the mullet with his gig.

Ask any fisherman, you can’t spear a mullet. They’re too quick, they see it coming. But David had learned to outguess them. He’s just set his bearings and let the praam drift under there, him with gig poised, and in the one short pass he’d select one particular shadow from the wavering rippling school of shadows, the lumpy water, and throw hard just to the right or left of it, and he’d feel the prongs jam into the fish’s bones about half the time. And the little death dance of the gig pole zigzagging as it sank, wagging the slack in the line, before he hauled in his catch.

But then he’d have to paddle back under the bridge against such a turmoil of crosscurrents from the massive concrete pilings that supported it—the bridge squatted on them like gross swollen ankles of a great slob troll that he had to be careful not to wake—while the currents gurgled from little roiling hills and sleeky whirlpools, reflecting oily amber shadows on top of darker ones, everywhere, with the water echoing everywhere, too, as if it lapped above and beside him as well as below.

It was too late to come down now. He closed his leaf bower and pulled his feet up and held very still. He saw why his father had moved Lorelei: it wouldn’t do to have her down there watching the police drag their hooks and nets across the bottom of the canal seining for his drowned body. He saw why Concrete and Jonah had retreated, maybe flown. They were embarrassed, all four of them: his parents because their son had drowned and Lorelei was in on that somehow, and his imaginary friends because of Lorelei, too. She was a girl. He thought of her the day they’d brought her home, tall and bald and naked and no one seeming to mind, except maybe, probably, his two best friends.

He listened a while to the police boats churning against the straining winches, the chains pouring rip-and-clang off the steel decks. He saw his younger self looking up into his tree and remembered now how they had talked, he and Concrete and Jonah: they hadn’t, but he’d been able to tell his mother everything they said. Now he couldn’t tell her anything, or wouldn’t any more than he could tell her about Lorelei, or Blainey for that matter.

Why? Because for one reason she thought he was at this moment drifting along the bottom of the canal out into the bay, and she couldn’t know how free that was, and that was the other reason. Get free of the adults, get away, like the gulls—where do they go when there’s no more fish guts to throw them. When David dove for sand dollars, his mother and the rest of them lying on the shore not thirty yards away, he’d test below himself with the tips of his toes until he brushed against the undertow. I was like testing the edge of that straining space between the Scotty dog magnets, and he’d take a breath and slip under and let himself be dragged into it, and be swept swiftly, his nose inches above the racing sand until at a bend—he knew the bends by the way the current tipped him as it curved, putting him near the edge of it, so if it didn’t spew him out it took only one snap stroke to break free, and buoy up to the surface. Gulls ride the air currents, and paunchy-chinned pelicans—why not a boy gliding away over the ocean floor?

But if he were drowned, he would not be able to snap out of the undertow, not sail over the ribbed sand bottom like an ace dive bomber, not watch any of this serious show beneath his tree, close enough to ping with berries, because the eyes, David, would be closed and the mother crying and the mullet getting even, nibbling on your wrinkled white, receding feet.

Boy, was she going to be surprised.

But she wasn’t. Somehow they’d seen him crossing the yard in the dark. When the boats and the frogmen had gone, and the last police car had slammed its door and crunched out of the gravel driveway, David had gotten cold and hungry and cramped, and had climbed down and trudged through the dew-damp grass back up to the house. When he walked through the door his father had been hiding just inside and caught his arm and walloped his behind, one, two, three four five all the way to the stairs, actually beating him, his mother yelling and crying, them yelling at each other, hugging him and brushing the hair out of his face, peering into his eyes to make sure it was him, that his eyes were open and not sockets, little empty scenes with a puff of sand kicked up by a startled fiddler crab.

And yelling why and where and finally everybody crying, all three of them hugging together, the dog barking and then cowering under the table afraid they’d all gone mad.

The next day they didn’t even talk about it, nor the day after; he played with his soldiers and knew not to ask if a friend could come over. It was like being sick. Life in the dog house, his dad called it. But that weekend, things swung back to normal: they were going sailing. With sandwiches and beer as usual, but also with cement building blocks and a coil of that nylon rope clear as a jellyfish’s jelly and Lorelei face down in the bilge.

They didn’t mention her. They barely asked him if he wanted to come. He did not. They wouldn’t be two hours, they said. A short run down past the County Causeway and out Government Cut. The ocean. They were breezy about it, gave him a number to call if he needed anything, but David knew: on “Victory at Sea” he’d seen the weighted coffins wrapped in American flags sliding into the sea. He knew he wouldn’t see her again.

But late that day, a strange thing happened. His parents didn’t come home when they said they would. It grew late and later, the sun sinking behind the bridge. David was on the dock, not waiting for them, just kicking around, pelting jellyfish, when there was a breath, or a whisper, but a big one—expelled!—and in the water underneath the bridge almost in silhouette, was a woman. Her long hair plastered back the way a woman emerging from underwater fixes it out of her face, this woman in the shadow, emerged, rose up holding still as if standing on a surfacing submarine. Then she sank back down, to just the top of her head, her face under, maybe looking for fish, under that terrible underbridge, tarpon as long as your boat, barracuda as thick as your leg. She was either crazy or in big trouble.

Furthermore, when she was up—the back of her head and shoulders—he couldn’t see any straps. His parents, and their friends, at parties sometimes skinny-dipped in the canal, at night. But no one . . . Not under the bridge, not even in daylight. Not without a suit on.

It was possible. Lorelei was certainly in the sea by now; with currents and tide in her favor, and a strong headwind to delay the sailboat, she could have beaten them home.

“Ma’am?” he called. He wouldn’t use her name. It couldn’t really be her; it had to be a neighbor, or a stranger, some landlubber from the Miami side of the bay, caught in the eddies under there, needing help. But his boat was out for scraping and painting…

“Are you all right?” He couldn’t get any closer because the fat concrete piling blocked the view from over on the seawall.

Then she stopped bobbing and sank all the way under. David was frightened. Even if he did dive in, grope around, find her in the blind water under there and pull her to the edge of the canal, the low tide put the top of the seawall out of reach, a good four feet above where they’d be treading water or standing waist deep in their bare feet on the coral rocks and sharp slippery barnacles, and she was naked. They would have to wait there until the distant putt-putt of the motor and then the prow of his parents’ boat appearing around the far bend at the open end of the canal. Then he could yell for help, but what would he, and she, talk about meanwhile?

Anyway, drowning people grabbed and choked you, mashed your face up against their bodies and dragged you down with them. Stay away, talk them in if possible, slug them in the jaw and knock them out if you must—rules as fast as not swimming for at least an hour after eating.

She had eaten within the hour: she was drowning. The bridge under there, the giant’s throat was gargling her. No, she had drowned and was bobbing upright, for days maybe, some springy undertow playing her out by her heels, and she was very dead. As his eyes adjusted, the bridge couldn’t hide it from him any longer: her skin was dark gray.

David kept calling and the fear in his voice scared him more. Brave or not, he wasn’t going under there with a gray and naked, drowning, whispering dead stranger lady from downtown Miami. If she didn’t hug him to the bottom, to stay . . . Then what? Then he might do it himself, to stay. That was what the German sailors swam to ruin for—the ones down inside the submarines for months in the war, their skin the color of a fish’s belly when they finally came up—for Lorelei.

Too long down now. She was gone. She was bumping along the bottom.

And then, poking out from under the dock, directly below him, coasted the biggest sea cow he’d ever seen. With its pear-shaped snout and head, and its gray body, moss waving out when it stopped, it floated its head up and exploded the air from its nostrils, and David nearly fell in. He seemed to teeter there about to fall on top of it even as he ran for his gig. The manatee moved along the seawall, just beneath the surface, feeding, making easy waves with its bony platypus tail, which was about the size of a manhole cover.

David on the seawall now, back a little where it couldn’t see him, hardly more than the gig’s length away. Point blank, he closed his eyes and threw at the back of the sea cow’s wrinkled folds of neck, just below the skull. He’d read they shoot alligators there, from behind the skull so it bowls up under. He wanted to feel his prongs snag in that manatee’s brains.

There was a tremendous whoosh. Nothing that big could move that fast, but it did—it must have seen him take aim. It heaved itself out of there with its massive tail displacing so much water that for a split second—this is what he remembered most when he tried to tell his parents—just for a second David could actually see the glistening mud bottom of the canal as if the whole bay had emptied and he could walk there, fearless, among the likenesses of fish.