Knock, Knock: A Deconstruction

The man was a story-teller, even in his immodest hospital gown. I’d helped with his spinal in pre-op and he’d kept us entertained all during that poking, wisecracks about being on needles and pins and stick it to me, doc, and so on. I don’t do him credit: you have to have been there: a happy guy, he had a charm.

But now he lay there with all of us on the surgical team converging around him as if he were the carrion and we the earnest jackals, he the calyx we the busy bees, busy with our sundry assignments but still vaguely listening to him, too, somewhere between in-spite-of-ourselves and half-seeking permission of the surgeon. The man.

It’s hard to tell of course, with everyone in surgical facemasks, just what someone is thinking, so you learn to read shoulders, spines, the tensing of an eyebrow, the pace of hands. Survival depends on this. Not talking about the patient’s survival. I mean that of the various nurses, interns and residents, their professional survival. You have to read the surgeon, else you won’t be on his next case, and grace too many of those black lists, you wind up in Laundry.

“So the girl doesn’t recognize that it’s a boat,” says our patient, “and she begins to change her clothes right there on the afterdeck. But the pilot, up on the draw . . . drawbridge . . . ” and maybe the word “says” ekes out of his mouth, as in he says or she says but that’s it. Full stop. Like some sort of hit-and-run knock knock joke, that all too rare breed, Knockus interruptus.

A couple of us had seen the pentothal go into the IV and knew what to expect—it does stop a large body cold before you can even reach five or four (counting down from ten)—but the surgeon had been bending the steel hip plate, with his bare hands, mind you—they give you some bending irons for those things, but orthopods, marvelous carpenters basically, have arms like blacksmiths—and now our chief with the gorilla forearms fairly glowered at the anesthesiologist, Dr. Peters.

“You take down the rest of that in Recovery, Bob.” He isn’t kidding. He wants that punch line. Something in his mood—we all read him plain—depends upon it. And because we’re a team, we all feel it, we want it too. This story, who knows, it may be the story that will change everything, for somebody.

But the gasman’s eyes are smiling, and so we’re all smiling; there’s just too many of us against the Knife to be intimidated, to worry about such transcendent secrets, and besides, I’m feeling proud and prepared—I’ve got my sponges and clamps and stuff he hasn’t even thought of, got it all ready to grab and slap into his open hand, and suddenly the patient heaves mightily. This wave runs from his chest right down to his feet. Was it an aftershock of the drawbridge? Boat hit the pilings? Half the stuff already laid out on his chest clatters to the floor, and the cute new circulating nurse is startled and steps down from her little stool, which she shouldn’t have been up on anyway except as a new girl, eager, curious, she wanted to observe, wanted to appear eager and curious, impress me maybe—I think in fact she has an eye for me—she steps down onto the waste bucket, or rather, into it—I can’t quite see from my position across the table from her, even with my higher perch as scrub—this being the moveable trash-bucket-on-wheels so you don’t have to handle it, just scoot it around with your foot, and she goes skating off on its smooth silent wheels into the second table, all the second stage instruments, for the second part of the operation. The surgeon swears and the anesthesiologist is now frantic. Patient has vomited and the tube is clogged so he’s going to intubate.

I see this expanding disaster in dream state, but my muscles resist any slow motion because I’m trained to react fast and not contaminate my table and so on, but the nurse is new and inexperienced, a big part of her cuteness, in fact (behind that mask), (and the pin curls from under her cap), and she grabs at the equipment table which is of the tall variety because Dr. Walkers is tall and also because she doesn’t want to go down (anything below waist level and you have to re-scrub, re-gown, etc.), so she clings to the drape sheet which catches underneath the table on the other side somehow and the whole thing begins to tip slowly over—could I have caught it?—the idiot won’t let go and it tips over onto her, crashing into Peters on the way down, who is just then busy cutting into the man’s esophagus to insert the intubation tube so he doesn’t see his close little world bursting into a storm of about a hundred steel instruments, little pans, needles, sponges, snaps, clamps, screws, chisels, gouges and so forth come raining down, followed close behind by the 200 pound stainless steel table.

This is a big man with a big heart and the little geysers of freshly oxygenated blood are pulsing steady reaching to about five inches high and the guy will go into shock in another minute, half that, if he doesn’t just completely bleed out first.

So much for contamination: we’re all scrambling now and the sweet circulating nurse is bleeding too, a gash over her eye; both doctors are swearing, I’m opening packs of silk sutures of various sizes and I can’t find anything on my table because Walkers has trashed it grabbing for a long clamp and you can see in a glimpse, the man’s slack chest and arms are fish belly white and sinking toward cyanotic green, the elysian fields of peaceful sea grass and kelp, not a color you ever want to see on your operating table.

This is going to be a bad day. I just happen to peek at the guy’s blood-smeared chart—my training again—we’re taught to check everything, over and over, and it pays off (check out nursie, for example, her blouse popped a button)—peek at the—where’s it say—the chart, just before they slam the units of blood into him, and what we’ve been sent is B+, while this chap, according to these stats, is A+. I announce this.

You never see a surgeon lose it. They get mad, rupture-furious even, veins in their necks and all, but they maintain control in mid-torso: they really do have great hands, arms, elbows, and pockets of their brains are as steady as crash-free data bases. Dr. Walkers, however, screams Fuck it! and throws one B+ unit across the room, so you’d expect a water balloon type explosion but this is hemoglobin in thick poly-something-or-other-thane and it bounces with a smack—he might have thrown a mackerel—and it slides across the red slick floor back toward our table. Please don’t step on it, too, I’m thinking, my cute little nurse skating across the room, in a cute little skating skirt, riding a bag of blood on a tide of blood, fishily into my arms, I’m actually savoring this thought, when as if to chide me the monitor starts its beep-boppy panic.

So now the guy is dying. He’s going into shock from blood loss and Walkers is screaming GET THE CART. Ten seconds… fifteen… of that terrible solid tone, flat line, the shortest distance between life and death. A liminal truncation: awful, it makes you hornet mad and hyena crazy. It makes my mind’s eyes cross.

Guess what. There are two cardiac arrest carts on the surgical suite and both are in use. So Walkers reaches for the ceiling like he’s calling on a god, and slams down on the man with both fists, held together like a hammer; it’s enough to shatter his sternum. The guy bucks once and coughs, and starts breathing again. That’s one I hadn’t seen.

They clamp his artery and tie it. Walkers is raining sweat but the nurse is too afraid to get near him, to wipe his brow. “Wipe,” I snarl at her, point with my eyes at Walkers.

Then the blood arrives, A-positive, and a crash cart is wheeled in, obviously unmade. We use it anyway: the heart stopped again and this time we skip the Thor act and just zap him. “Clear!” all that. It’s a good heart and kicks in again first try.

My poor nurse is not much good, however, crying, useless, has enough sense to get out of the way at least, shouldn’t even be there in that kind of shape but now is not time to ask the surgeon for permission to leave, she huddles in a corner on the floor next to the loose bag of blood, and then is helped up and led out by the head OR nurse who’s heard the commotion all the way down the hall, and who then returns to circulate for me.

“Sure could use some silks,” I tell her.

I get my silks, new hemostats, clamps, kellys, fresh packs of sponges—I have my own moment of panic where I miscount the dirty sponges, that’s all we need, leave a sponge or two behind, but on a recount with Nurse Dominick (who seems to like me, fortunately), we both get twenty-three, a number I have counted as lucky from that time to this. And finally the floor’s mopped and the smoke clears and we get on with it: originally a compound fracture of hip and femur, nothing a good carpenter couldn’t mend better than new, but this poor guy winds up with a code blue cardiac arrest, twice, three broken ribs, second degree burns on his chest and armpits (the metal ground for the cauterizer had slipped out of place), and a slit throat that damaged his larynx.

It was this last, the windpipe, the vocal chords, that scotched the joke. We learn the man’s vocal chords had “dissected,” which means separated, torn off at their insertions, and also some nerves had been damaged, almost severed, stripped a section of their sheaths, so the damn things were shorting out in recovery and we would have to wait six months, more or less, for things to reattach and the insulation to grow back, wait that long for woman on the boat in the joke to have her suspended moment with the draw bridge skipper. Though I suppose our guy could have written it out, if he remembered it. But I don’t mind the uncertainty.

Perhaps as the draw bridge operator raised the massive structure—the cars all stopped along the causeway, people stepping out for a smoke, some even turning off their engines, watching the boat slide through in the turmoil of back-currents beneath the underbelly of giant gears clotted with black gritty grease—our lady on the afterdeck, in the same testudinous ballet as the 50 ton machine, pulled up her sweat shirt, so her breasts flopped out, and some horns honked and the operator called down to her…

What? What would he say? She couldn’t have heard him anyway. And why wouldn’t she recognize it was a boat, if it was smack under a drawbridge?

Did they know each other, bridge captain and girl? Maybe he was her father. Who else was on the boat? Maybe it was my nurse. There were maybe a hundred of us up on the causeway (that’s where I place myself when I revisit this uncorked moment); was she just waking up from a night of debauchery at the Racquet Club, coming up on deck never having known she spent the night in a yacht’s forward bunk, playing footsie in her sleep with the oily ropes? Maybe she was acquainted with Dr. Walkers. I don’t think she was in trouble, really, not the way the patient told it, not if on the other side of that bridge there was a punch line waiting, is waiting still, and certainly not in the lazy way she pulls up her sweater, tosses it on the deck, steps into a shower of fairy dust.

I was nineteen then, and she’s been with me all my life since, and I’ve never been able to hear her voice over the dream roar of that troll-like bridge. Her breasts flop, the commuters approve, the bridge captain blasts his all-clear horn, and the raised bridge starts down again as the boat enters the outer bay, leaving us all behind.

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

It was this young woman, starting to change her clothes on the deck of a boat as it slid out of view beneath the opening jaws of a drawbridge, with hundreds of us watching from above, some even crossing to the other side of the bridge to see her come out, maybe by then having gotten her pants off.

Her-pants-off-who?

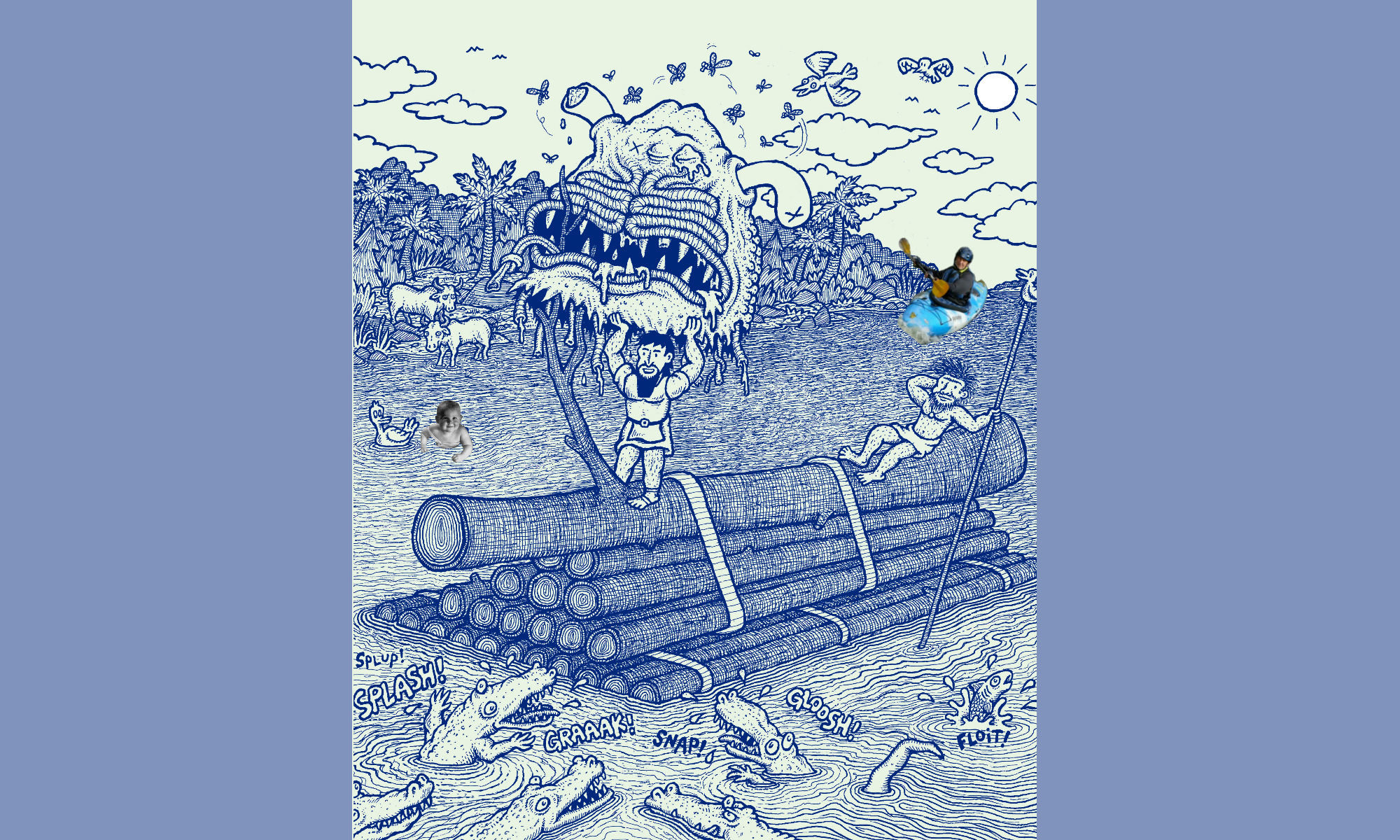

This was published in 2014, in the on-line journal out of the University of Virginia’s Medical School, Hospital Drive. It’s no longer in the Archives there. The Polaroid below is over 50 years old—1963. Walkers in the center. Actually dated the nurse later that summer. Beverly, you still out there?