Get Drunk

A flash fiction ~ by Charles Baudelaire

Trans. by Kent H. Dixon

It is necessary to always be drunk. That's all there is to it, that's the only question. Not to feel the unbearable burden of Time, that breaks your back and bends you to the ground, you must get relentlessly drunk.

But from what? From wine, from beauty or power, whatever. But do get drunk.

And if sometimes, on the palace walks, say, on the fresh green of a grave, in the gloom of your single room, you wake up, your high already fading, or altogether gone, then ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, ask anything that hurries along like these, anything that groans, anything that thunders, that sings, that speaks, ask it what time it is.

And the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, they will all tell you:

"It's the drunken hour! If you don't want to be the wretched thrall of Time,

my man, then be drunk, ceaselessly drunk. With wine, with beauty or power. Whatever."

Enivrez-vous

Il faut être toujours ivre. Tout est là: c’est l’unique question.

Pour ne pas sentir l’horrible fardeau du Temps qui brise vos épaules et vous penche vers la terre, il faut vous enivrer sans trêve.

Mais de quoi? De vin, de poésie, ou de vertu, à votre guise. Mais enivrez-vous.

Et si quelquefois, sur les marches d’un palais, sur l’herbe verte d’un fossé, dans la solitude morne de votre chambre, vous vous réveillez, l’ivresse déjà diminuée ou disparue, demandez au vent, à la vague, à l’étoile, à l’oiseau, à l’horloge, à tout ce qui fuit, à tout ce qui gémit, à tout ce qui roule, à tout ce qui chante, à tout ce qui parle, demandez quelle heure il est;

et le vent, la vague, l’étoile, l’oiseau, l’horloge, vous répondront: “Il est l’heure de s’enivrer!

Pour n’être pas les esclaves martyrisés du Temps, enivrez-vous; enivrez-vous sans cesse! De vin, de poésie ou de vertu, à votre guise.

COMMENTARY

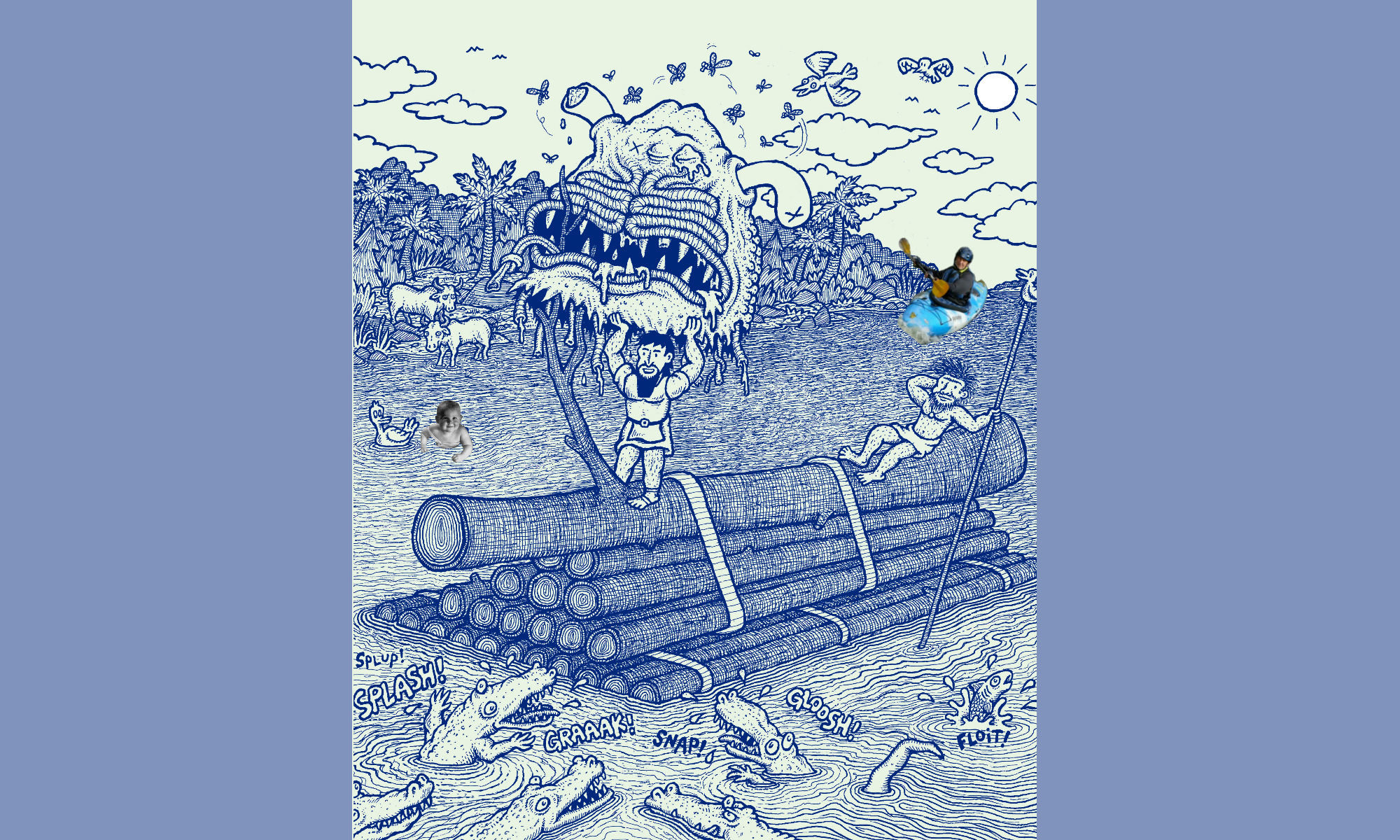

“Dr. Dixon Exhorts Students to Get Drunk” read the headline of the Torch, our University newspaper, reporting on a reading I’d given. And this prose-poem of Baudelaire’s, published in Les Fleurs du Mal, 1857, is a complete ball to read aloud. Much of Baudelaire’s poetry is ‘oral,’ colloquial, and the semi-dialogic performance is built into it here as Baudelaire strongly implies his own interlocutor: Mais de quoi: ‘get drunk from what’ (you ask)? And again, turning the one-sided colloquy (and choice) back to that implied listener at the two crucial points of listing to what to get drunk from: à votre guise (‘at your pleasure,’ ‘as you please’) which I must say I am pleased to have rendered into that supremely adolescent shrug: ‘whatever.’

So though I didn’t mean to translate this for students, it certainly speaks to them—their fardeaux du temps [their burdens, their teenage angst] as anyone who teaches knows, often far outweigh our own—and it catches them up with its suspense: what exactly is it we’re to get drunk on? Oh, poetry… I see. Poetry like this little paragraph—ah ha!

Which brings me to what I thought was the most difficult word to bring over: vertu. You are to get drunk on wine (fersure), poetry (oh, I see), and finally virtue?? Now this is the virtue of righteousness then, of doing the right thing? Yawn.

Is it manliness, is it mindfulness? It could be the properties of some thing, like the chemical properties (les virtues) of certain plants, and if I’d known I was writing for students at the time, I might have leaned past tipping toward the neurotransmissive properties of ergot alkaloids (synthesized to lysergic acid, di-ethylamine), or maybe just some humdrum cannibinoids, but it’s hard to get all that breaking bad stuff plus the hallucinations, down into one word, so as to keep the balance with wine and poetry. So I’ll stay with power, which with a little luck, subsumes some of the delusions of grandeur and persecution and reaches out to embrace who-knows-what a 20 year olds think when they hear the word ‘power.’ After 30 some years of teaching them, I shudder (as well as hunger) to think! And I wouldn’t mind seeing what Baudelaire was favoring either.

Here’s one I missed: demandez quelle heure il est, simply, When you hear the stars and the bird and the clock and the wind ticking away, Ask what time it is.

How about: Ask what time it really is, and sneak in a few bars of Robert

Lamm’s opening to Chicago’s “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is”?

Does anybody really care?

(If so, I can’t imagine why. We’ve all got time enough to die.)

Whatever.