This travel piece, a visit to Cuba in 2001, and not published till 2011, is arguably out of date. And yet it isn’t: the people are the same, or more so, and the main insights hold up, almost 20 years after the trip. It was published in a British journal, Studies in Travel Writing, the Taylor & Francis house doing a special issue, historic and contemporary, of the pearl of the Antilles, beginning with Alexander von Humboldt’s studies of the island’s slavery at the dawn of the 19th century! My piece shares with one other travel writer’s the contemporary slots: “…taking the temperature of Cuban society several decades after the installation of a revolutionary new order.” Not to panic at the historical breadth implied in my title: my Batista was an engaged Cuban exile who, after our interview at her apartment, graciously invited me to stay for dinner. And a lovely dinner it was, until I opened my mouth un poco demasiado (a little too wide), wide enough for both feet.

From Batista to Fidel, and on to the

Most Recent Enemy of the People

¡Viva la revolución!

By Kent H. Dixon

Cubans Are a Volatile People, Emotional and Opinionated

Her name was Batista—no relation to the dictator. Her apartment in Miami, on Key Biscayne, faced south east overlooking the ocean, wistfully toward Cuba. Between the array of docks below us and the horizon, tiny bright boats flecked the blue blue water, leaving white scratches of wakes like jet trails, all of it postcard pretty, and the interior of her condo was every bit as perfect—the leather bound books, designer furniture, crystal, silver, arresting art, and a white wine that whispered citrus. I was a stranger to her—the meeting arranged by a mutual friend, prelude to my trip to Havana in 2 months—and she had most graciously received me, though I suspect mainly to press her cause. I was a writer, after all.

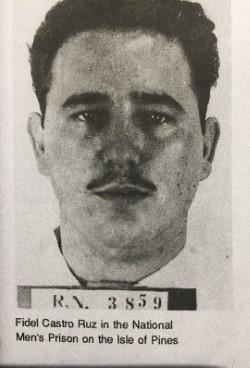

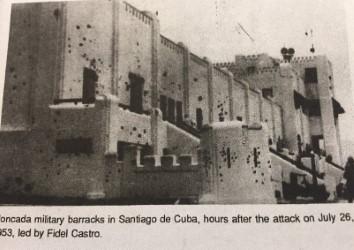

But politics wasn’t precisely my thing. I was headed for Cuba seeking local color, authenticating details and overlooked pockets of history for a novel-in-progress set in Miami and Cuba in the early 1950s.  But she was of the elite that he had been bent on deposing back then, before Che even, in late July of ’53 when with a hundred and seventy ill-trained he attacked an army barracks of over a thousand soldiers near Santiago de Cuba, disastrously for him as it turned out: most of his force was killed or captured (and tortured), and Fidel was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment.

But she was of the elite that he had been bent on deposing back then, before Che even, in late July of ’53 when with a hundred and seventy ill-trained he attacked an army barracks of over a thousand soldiers near Santiago de Cuba, disastrously for him as it turned out: most of his force was killed or captured (and tortured), and Fidel was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment.

“He should have been shot then,” she said. “That goddamn sergeant, I wonder where he is now.” [The reference is to the sergeant that found Fidel asleep, after he and his decimated rebels had fled to the hills, turning him over to the militia at Santiago instead of bringing him to Havana, where he wouldn’t have lasted long in the clutches of Strongman Fulgencio Batista.]

La Señora Batista decided to keep me—un buon’ escuchando (such a good listener)—for dinner and called her friend to come join us. Hermán must have lived in the building: not ten minutes later he’s letting himself in, armed with three bottles of wine and a somniferous loaf of homemade bread. He had a twinkle, you liked him right away, and our politics seemed closer: our talk of the embargo made those eyes of his flash—just the sublime arrogance of it.

It is amazingly imperious: not only do we not trade with Cuba, but any country’s ship that does, if it docks there first, may not then put in at any US port for six months.

“We don’t agree,” he smiles at me. “Oh, si si, it is a stranglehold ya seguramente an’ everyone gasping and staggering,” he gestures, clowning, and then dead serious: “But they clutch more fervor to the heart because of it. Cling to el leader,” spinning the l in her direction.

“We don’t agree,” he smiles at me. “Oh, si si, it is a stranglehold ya seguramente an’ everyone gasping and staggering,” he gestures, clowning, and then dead serious: “But they clutch more fervor to the heart because of it. Cling to el leader,” spinning the l in her direction.

She just says pooh—but Hermán’s version was exactly what I would see two months later. The embargo and the resultant hardships imposed actually work to sustain the revolutionary spirit, through two generations now, rather than causing the desired “hunger, despair, and the overthrow of the government,” to quote our US Department of State, 1960.

Imagine if you will a huge collective barbecue, the denizen of four square blocks gathering at mealtime at the main intersection bonfire to parcel out the collective stringy meat and rice and yucca: this is the way they fed themselves, all over the city, for most of a year after the Soviet Union disappeared in ‘92.

The blockade is simply war in one of its attenuated guises, yet the people are forgiving and—is this not patent after sixty plus years?—profoundly resilient. ‘We like Americans, we just have some questions about your leaders.’ I heard this so often when I got there that I decided it must be a reflex litany, pre-dating Roosevelt even, who, in an interesting historical aside here, nearly invaded the island with 30 battleships assembled off its shore and warplanes at the ready in Key West, in 1933 when his ambassador told him the latest presidente was flirting with Communism.

The complement to this reinforced revolutionary commitment is to be found in that second largest Cuban city, Miami, among the exiles, for whom every failure of Fidel’s program is a hope-inspiring victory and every success a setback. And my two Cubans-in-exile, willing testifiers, were ‘passionate and volatile’ to be sure (see Heading), if on opposite tacks: he was the lover, she the hater. He would actually defend Castro now and then, how he hadn’t begun as a Communist, or a dictator; just been driven to it, largely by US tactics. But she loathed everyone, furious at Cubans for acquiescing to the upstart lawyer, at Washington for its oppression and exploitation, and its failures—the Bay of Pigs; or Operation Groundhog, those bizarre CIA efforts to assassinate him (an exploding cigar) or discredit him by poisoning him so his beard would fall out—and furious above all at Fidel for stealing her world, which, she had no doubt she would get back some day.

“Just wait until he dies.”

Half of Miami is waiting for him to die of course. Maybe only then the rude awakening that the present cannot be the past?

“The revolution does not end with Castro,” an Economics professor at University of Havana assured me. That may seem obvious to the historically literate, but it’s not to the older Miami Cubans. Many harbor a hope for yet another military invasion, and, who knows, wasn’t it reported in the Bush era that we actually have invasion plans drawn up, for a Rummy day as it were? And whatever’s happened to good Joe Lieberman’s bill for 130 million to fund counter-revolutionary groups on the island to bring down the regime from within? Arrogant? Imperious? Who, us?

“The revolution does not end with Castro,” an Economics professor at University of Havana assured me. That may seem obvious to the historically literate, but it’s not to the older Miami Cubans. Many harbor a hope for yet another military invasion, and, who knows, wasn’t it reported in the Bush era that we actually have invasion plans drawn up, for a Rummy day as it were? And whatever’s happened to good Joe Lieberman’s bill for 130 million to fund counter-revolutionary groups on the island to bring down the regime from within? Arrogant? Imperious? Who, us?

My hosts and I were in the middle of Elian (this was in April 2001; the five year old from the inner tube had returned home a whole year before), when things got out of hand. I was agreeing with Hermán: a child should be with his remaining parent. She rolled right over him with her juggernaut of abstractions, liberty, justice, freedom, etc.—the kid had been on holy ground and ties to his family and country be damned. I tried to arbitrate, but they ignored me, reduced me to the little boy numbly watching his parents crank up the decibels, slam the cups in the saucers and stab the air with their forks, until, afraid it would come to blows, I said, “Hermán is just saying a little boy is only a little boy. He shouldn’t be made a symbol at his own expense…”

“A symbol?”

“Well, yes, sort of. The whole exile community, their own lost little boy innocence…?”

Silence. She looked at me, hard: something had just come clear to her. “You are with him, aren’t you!? You are with them!”

A sympathizer, in her kitchen! She felt violated, she clutched her breast. Wining and dining me, trusting me enough to show me her family lineage in the great book of the Conde de San Juan de Jaruco. (Most every Cuban I spent time with in Miami showed me their family name in this book, some sort of endless genealogy of Cuban families, a Descendants of the Mayflower but predating it by a century at least, usually branching back to Spanish royalty. Velázquez slept here.)

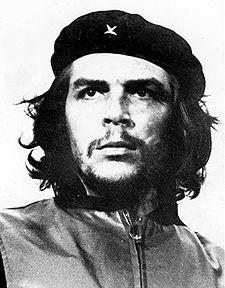

I draped my mouth in apologies, said I’d only been a college kid in 1960, smitten by Che, favoring the underdog, superficially involved with desegregation on my own Chapel Hill campus, identifying with the freedom fighters, the blacks, the workers of the world, the wretched of the earth.

“I’m a political romantic,” I excused. Was then

and still am. Really, what’s a sugar plantation or two

(or two dozen) in balance with social justice, universal medical care, literacy, education, representation, land ownership? Viva la …

“You may leave,” she said, nearly toppling over from the height of her indignity, pointing my way back out into the stormy socialist night. As the elevator closed, I could hear them start up again, across the little terrazo’d alcove and behind the ornate and very firmly closed door.

The economy is in shambles and everyone is a hustler. The jineteros will rob you blind.

Two months later I’m in Havana. I piggy-backed on a contingent of fellow professors from my university, who were visiting Havana to evaluate a program for our students and to do some research of their own. Most everything was arranged for us and everyone except me spoke some kind of practicable Spanish, though even professors of Spanish have some trouble following the Cuban. (Native speakers drop more than the final s, bl’v m’.) But it was a perfect arrangement for my research on my novel, and given my language handicap—only one semester with Mary, one of the evaluating professors—I couldn’t have been better bolstered. Besides, I’d wanted to visit Cuba ever since I missed my class trip from Miami Country Day School in 1953. Something about Moro Castle and sharks, the Count of Monte Cristo and the seventh grade.

The women were shopping, in Habana Viejo I think we were, and Rick and I were wandering in sidewalk limbo, waiting for Mary and Joanna.

Hey, buddy, you my friend, you my buddy, norte Americano, Elvis, my good America buddy, his hand out, his cap turned backwards. This was the first jinetero I’d encountered up close, real close like he was attached to us in a sidecar. The word literally translates jockey. We kept walking, but the man swung around in front of us: Buddy, you wan pesos, you wan cigaros, rum, amigo, mi amigo mi buddy, girls, I got girls I got cigars…

“Nada,” says Rick, stern. Waves him off. We move on. He follows, he’s beating the air with his baseball cap, fanning his rant. American buddy, you like Elvis…? Heningway, you like Henigway…?

Rick turns on him, very stern, like ‘next step is I punch you’ and says Nada again. I’d never seen Rick even frown much less smolder. He is lithe and part Asian, can look inscrutable ergo dangerous, with those dark drawn brows. For his own sake I hoped our jinetero got it, as we walked on.

He stopped following but after ten yards he began to yell at us: Fuck you, buddy. Fuck you! Fuck Elvis, fuck tanto samo, you big fuck, norte Americano, fucking Yanqui, you go fuck youself…

Who knows why I do these things: I wheeled around and went back to him. He stiffened, ready to fight. “Pero usted dice I your buddy,” I said, plaintive. “Nos somos amigos, norte americanos y cubanos, buddies, bud-dies… Que passó?”

He was stopped momentarily, and then he laughed, beat the air some more with his cap. You no wan’ trade peso, hey?

I laughed, said I didn’t, asked him if he came from Havana, ori’hinalamente. I wanted to know more about the southeast, Santiago de Cuba and the Sierre Maestre, for my novel, but I hadn’t found anyone yet that wasn’t native Habañero.

Where was I from? Ohio. That confusion of foreigners about Ohio and Iowa. Well, I lived there, too, once, in Iowa.

You caballero..! Cowboy, and on about American movies and John Wayne, Iowa bordering on California in his mind, same as Idaho. No point in clarifying, our mandate seemed to have been to cover territory, share common ground. I was a professor; he was an electrical engineer, but there was no work, no jobs. His wife was a translator. Es porque ton buon Inglese, no? I said. His good English.

No. She spoke Russian and some Chinese. Swahili. I should come to dinner. Did I know the plattes?

Pratess? Platterrs! Si, si. Oh, yes, I’m the great pretender… P’entendes oo abadón … he didn’t have the words, but the tune was right on. Curiously, given all their illegal radios, their rock is like their cars—Elvis, Temptations, Platters, Johnny Mathis… In 2001 it didn’t seem to get much beyond the 1950s.

Iss America racismo?

Ugh. Yes and no. “I’m white,” I said. “In a university. No es malo, pero… not like los chinquantas, in the fifties, but it still goes on,” nodding yes. “Y tu? Here, por aquí?”

He thought I was asking about him, his color. Ay, aquí, in a lilt that indicated quotation, Mi madre e negro, mi padre e blanco, yo soy Cubano. My mother is black, my father is white, I am Cuban.

On this note, I must say, watching the groups of Cuban students that took us everywhere on bicycles, a dozen or more on any given day, a changing mix of whites, blacks, redheads, blonds, 31 flavors of mulatto, I saw absolutely no social distinctions, no division by “race.” And we were with these kids a lot, eating in a park, or crammed in a ferry amongst our bicycles, or singing in a bar, dancing in the street, or, one of my favorite afternoons, crowded under a large awning drinking mojitos in a sudden tromba de agua, a tempestuoso thunder storm across the harbor on Casablanca, all of Havana laid out before our grand toasts and sundry common songs—Frère Jacques, Guantanámara, La Cucaracha…crash, like cymbals, the buckets of downpour sliced by fissures of lightening, porque no tiene—good feeling, arms around shoulders, international brotherhood—porque no tiene, marijuana que fumar! Only I’m pretty sure I smelled some, unlike el pobrecito cockroach. Surely there are social lines in Cuba, but they don’t appear to be drawn by color. Not with the young at least. This no doubt results from inter-mixing after the white flood: the exodus from the revolution in the early 1960s was almost entirely upper and middle class—the peninsulares and the criollos, the Spanish-born and their “creole” descendants. The ones with the most to lose, taking their class distinctions and lighter skin right along with them. And the descendants of those left behind have grown up together, color blind as children—maybe a little something right with the world for once.

Cuba’s race history is certainly no better than ours (slavery abolished 20 years after our Civil War), but the revolution was a lot about race. Not a new story for either country: one reason the U.S. didn’t buy Cuba in the mid-19th century was that it would have come in as a slave state, so that initiative was quashed. (How capricious is history: four other attempts to purchase the island were made by the US in that century, all rejected by Spain. What a difference a little si would have made.)

So Sandino and I sat on the warm steps in the blanching sun and chatted on this way, good buddies, compañeros for at least half an hour, practicing my Cuban (¿Que bola asseres? great Cuban slang for something between How’re they hanging and Wha’s up?) and his English, I can give you a tour of the city, Only 20 dollars, Take as long as you like) until Mary and Joanna appeared, asking for Rick. Sandino pointed to a shop half way down a very long next block: what an eye! I’d seen Rick disappear into one shop, but not that one, not that side of the street or even that block, and Rick was my way home. My jinetero was a keen observer.

We shook hands, we embraced, and then he did the Cuban one-cheek kiss. If I was going to be fleeced, this was it. But my wallet was there when I checked and I’ll leave the reader with my dilemma: After this impromptu camaraderie, these two citizens of the world hitting it off, and in full appreciation of his difficulties (his wife couldn’t be translating much Russian these days), did I give him some money?

The children are taken away at age 5. They are brought up in special schools away from home, in camps, where they are brainwashed.

My familia Cubana, Marta and Luis, had a 12 year old son, almost 13. Randy: pronounced RAN-DEE, equal emphasis. The household was a caffeinated love-fest. Before bed she would bring me un copita of Cuban espresso. I don’t think I slept that week. Luis went to work before six, and woke me to share un copita of Cuban espresso. We talked a lot: I was a favored guest, not a border, though I seemed to hale from another century: I had the depressing impression they were like primitives, incredibly sweet and naive, little brown brothers childlike to a forgivable fault, to judge from content analysis, until I realized we were necessarily operating at my own beginner language level! A metaphor for our Latin American policy, I propose.

But Randy had not only not been farmed out at five, he was a much loved only child, with more than a few signs of being spoiled. Mama did everything. Luis I think was a step-dad, so the authority was tricky. And when the kid wasn’t watching boxing or old American movies on TV (dubbed into Spanish, with English subtitles—go figure, but great for my Cuban and translation funny bone: ‘You must have that!’ Bang, bang.), or tinkering with some poor man’s Nintendo gadget that held its charge for about five minutes, he was in my room fooling with my cameras and books and flashlight and penknife. He coveted my long cargo pants, with all the zipper pockets; he had only shorts like most pre-teen kids, a state-imposed savings on cloth. I couldn’t shake him.

This was early June, and he had school for another week. He showed me his math, which somehow seemed foreign. I hunted for a statement problem, hoping for some socialist realism offering itself to be organized by distance, rate, and time, but no luck there (par for me and math). So we watched boxing and American movies I can’t imagine anyone ever saw, and talked fútbol and tried out various moves on each other, using a wadded up paper bag para la pelota. He was agile and we had genuine house-romping fun before mom got home. But I couldn’t really work on my notes, for my shadow. He sorted the photos in my wallet over and over, each night, with my equipment spread out on the bed, not really knowing what he was looking for. I gave him most of my loose stuff and all of my batteries when I left, but that probably just whetted the desire. He’d been brainwashed all right: what he wanted was materialism.

He is through his teens now, Marta tells me in a yearly email, and very tall. I should have left him those pants.

The police are everywhere. Big Brother is always looking you over.

They lived in an apartment building that Luis himself had helped build. In return for his three years of labor, he got the apartment—three bedrooms on the 8th floor (above the mosquitoes), with kitchen, bathroom (shower only), narrow living room continuous with dining space, and some closets. Not much junk; in fact, quite sparse. In a week I’d learned every noun in it. He worked in a boat yard that you could almost see from the balcony, down some twisting canal a ways, I think part of the Almaderes river that separates the posh Miramar section from Havana proper, and one morning after he’d left early and me wide awake, I decided to hit the 6:00 a.m. streets and pay him a call.

As it was, I had spent most of my nights staring out my eighth story window, over the city off toward the immense Plaza de Revolution, getting a plan of the city and soaking up the conversations from the street below, which never abated and drifted up to me as clear as if in the next room. The thrill, about my fifth night there, when I began to get the gist—some talk about a bus line, or was it some family crisis? Close enough. It may be that the Cuban tongue slows down at 4 a.m., waxing philosophical, reflective; or, maybe even they poop out toward dawn.

Not me. Energized on espresso and Cuba, I dressed in the dark, gathered my key, camera, wallet and city map, and slipped out the door to go surprise Luis.

I was near the canal, I could smell it, when six soldiers suddenly surrounded me. My minimal Spanish evaporated, visions of a Mexican jail and Before Night Falls. They might have been police but I seem to remember rifles, camouflage gear, polished boots and holsters. Yo soy norte Americano, estades unitos. Elvis? Habito alla, over there, in edificio grande, sonno professore, university, universidad? L’université américain... habla ustedes franchese? They didn’t speak French, and they didn’t speak English, and the only thing that saved me, I think, (from what?), was the color xerox of my passport that I carry.

Turns out—not that I understood this from them—that I was in a restricted area. The canal is used for military transport until eight in the morning. Luis was most amused that night when I told them, Marta alarmed. But save for one other traffic cop, and some officials with drug dogs in the airport (black cocker spaniels, so cute you had to suppress petting them), these were the only police I saw all week. Are they all plainclothes then? I think Big Brother e echarsando mucho las siestas—must take a lot of naps, because He was pretty scarce that week.

The people of Cuba, bowed by suffering and pain,

Have decided to struggle until they find a real solution,

. . . determined to risk even our lives for this cause.

¡ Viva la revolución !

If you will, turn back sixty years, to that time of the raid on the Moncada garrison, July 26, 1953. Fidel had learned that one of his 170 recruits-in-training was a street singer and sought him out at target practice to ask him to compose a song for their revolution. “Something epic,” he’d said, as told to me by the very singer/song writer himself.

If you will, turn back sixty years, to that time of the raid on the Moncada garrison, July 26, 1953. Fidel had learned that one of his 170 recruits-in-training was a street singer and sought him out at target practice to ask him to compose a song for their revolution. “Something epic,” he’d said, as told to me by the very singer/song writer himself.

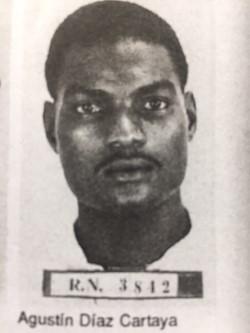

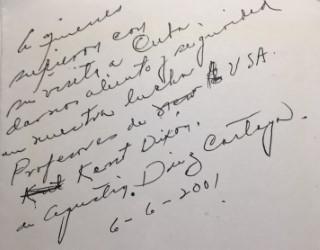

Agustin Cartaya, half a century later still looking like every Black Panther’s dream of himself, is an immense man, handsome, about 80 now with the close grey-white hair that looks so great on black men, the white beard trimmed. Muy guapo, muy bueno (handsome and totally cool). He was wearing a black t-shirt with a huge lion’s head on it, and a gold cross hung from his neck, sort of like a key to something, though to what I couldn’t say: he was inscrutable behind dark shades. His movements were languid and precise at the same time, even with the slight limp.

Agustin Cartaya, half a century later still looking like every Black Panther’s dream of himself, is an immense man, handsome, about 80 now with the close grey-white hair that looks so great on black men, the white beard trimmed. Muy guapo, muy bueno (handsome and totally cool). He was wearing a black t-shirt with a huge lion’s head on it, and a gold cross hung from his neck, sort of like a key to something, though to what I couldn’t say: he was inscrutable behind dark shades. His movements were languid and precise at the same time, even with the slight limp.

He’d been a 19 year old cantante in 1953, an orphan with a guitar, a tough. He was one of only four blacks to be part of that first faulty step in the pre-revolution. He was among the twenty-six or so that wound up with Fidel in the prison on the Isle of Pines, serving a term of from 10 to 15 years, having escaped being killed in the attack or executed at Moncada promptly, or tortured to death in the first weeks after their arrest, like so many. He told us—three American professors from Ohio—wonderful and stunning stories. How the revolution really began in that prison, la prisón fecunda (the fertile prison), where they were allowed books and educated themselves for almost two years before Batista, under mounting public outcry (and considerable pressure from the Catholic Church), let them go. How they communicated with the outside—notes on rags wrapped up in a rag ball, accidentally batted over the wall; or within a song, changing the words or the order of stanzas—how they kept their spirits up, learned discipline, sang Agustin’s freedom march when Batista visited the prison once on his birthday, so to spend yet another month in solitary.

He limped because of the tortures. They didn’t pick him out very often: he was so big it took six Cubans, but when they did, they really went to town. I liked his freedom-day story: unconditional amnesty for the moncadistas is granted and after 22 months, they are released. Guards conduct Cartaya to a police station in Havana, to do some final paper-work and the police chief, who knew him from the street and hated him anyway, said, Adios, muerto. Good-bye, dead man. This was an official who had bragged to the mother of a young revolutionary he bumped into on a bus that he’d gouged her son’s eyes out that very morning.

Two secret police followed Cartaya outside and down the alley. He was weak, coming off a hunger strike and beaten badly the week before, and he knew he couldn’t last long, nor could he run, as they closed the distance between them. His freedom seemed awfully short-lived. So he turned back and accosted them. He had no money, he said, and asked them for some pesos. It worked. They said he had cojones, gave him some change and followed him no further.

At the end of our visit, Agustin and his wife, and another couple (the man also a veteran of Julio veintiséis), lined up to sing Agustin’s revolutionary song, which is now the national anthem. I video

At the end of our visit, Agustin and his wife, and another couple (the man also a veteran of Julio veintiséis), lined up to sing Agustin’s revolutionary song, which is now the national anthem. I video

taped it, as I had most of the interview. I’m shy about thrusting cameras at people anyway, and though deeply moved by the moment, as we all were, a ringside reminiscence of the dawning of the Star Spangled Banner as it were, I also wondered if he resented us, felt like a monkey on display, forced into making a living out of being a founder of the July 26 Movement. But I got it on tape nonetheless, pure and moving, and current. Absolutely vital, exactly what I’d come for in fact.

When I shared this with the head librarian at the Biblioteca Nationale, how these incredible historical resources like Agustin were floating about the island yet with no one taking down their story, such a treasure of oral history on the verge of slipping away, the very youngest of them now in their seventies, she became defensive and gave me a curious answer. ‘In Cuba, we do not write biographies of the living.’ It took Rick, the Political Scientist, to explain this to me: he weren’t famous yet, the revolution ain’t over, history could change, the stock of the moncadistas could go down, down, down.

Not in my book. I had him immortalized on tape and he’s become a character in my novel and someday I will go back, armed with adequate Spanish, to save Cuba for the Cubans, these mal-historically minded, so inured to the absurd, world-weary and ever hopeful, ever skeptical always buoyant, surpassingly admirable Cubans.

Not in my book. I had him immortalized on tape and he’s become a character in my novel and someday I will go back, armed with adequate Spanish, to save Cuba for the Cubans, these mal-historically minded, so inured to the absurd, world-weary and ever hopeful, ever skeptical always buoyant, surpassingly admirable Cubans.

On or before June 2, 2001, you purchased a travel package through ______, which included roundtrip air transportation between Cancun, Mexico and Havana, Cuba. While in Cuba you engaged in travel-related transactions, including paying for food, drinks, entertainment, ground transportation, and incidentals.

Oh, oh. The tone didn’t sound much like a polite interrogative, this billet not-so douce from the U. S. Department of Treasury, arriving in my mailbox some four months after we’d returned to the states.

You don’t really have to declare you’ve been to Cuba, when you touch back down in Houston from Mexico. The passport stamp is so small, half the size of a postage stamp, that it’s easily missed on a busy passport page, and if your Spanish is up to it, you can ask them not to stamp you at all at the Havana airport. We would have breezed on through, but Mary said, Let’s see what our students (returning two weeks later) will run into, and Rick said why not, and I was so used to clinging to their coattails anyway, my interpreters, that I didn’t think to cast off now. In fact, Houston seemed more foreign than Havana or even the remote and lovely Mexican fishing village we’d laid over in for two days, south of Cancun. So when asked if we’d visited any country besides Mexico, we all merrily said, “Cuba.”

You’d have thought we said, “Stick ‘em up!”

From my vantage I could see half a dozen or so stalls, each with its customs agent, and every single one of them fell silent, every face went blank, every eye on us.

“Follow me, please,” dry, distant, like a cop being professionally polite.

Three hours? Four, five? I lost count. Rick says I was guilty jitters incarnate, when in fact I remember being fairly calm, because it was a technicality, no criminal or traitorous intent for our part, for sure. The agent breezed by all my José Martí literature and made notes about the two Che Guevara t-shirts (for my kids) and the guyabera dress shirt that Luis had pulled from his closet at my farewell dinner, and what’s this—a weapon?

No, it was a souvenir miniature fork from Marta because she’d insisted on giving me something and I’d been reluctant to carry all the French Impressionist reproductions on mat board that she’d hauled out. And Randy’s little keychain bauble, an alligator-in-a-shopping-bag that read: Yo Cuba. And the used books, pamphlets on collective farming, coasters from famous bars. That’s trading with the enemy, buddy, if your papers aren’t in order.

No, it was a souvenir miniature fork from Marta because she’d insisted on giving me something and I’d been reluctant to carry all the French Impressionist reproductions on mat board that she’d hauled out. And Randy’s little keychain bauble, an alligator-in-a-shopping-bag that read: Yo Cuba. And the used books, pamphlets on collective farming, coasters from famous bars. That’s trading with the enemy, buddy, if your papers aren’t in order.

Ours weren’t. Somehow the organization under whose auspices we’d traveled hadn’t renewed a certain license, really an oversight, really a function of the government’s delays in responding in a timely fashion to a routine filing, really probably set up by the government, gambling on the possibility of the organization’s not catching one missing signature in all that paper work, but whosever fault, we were the ones left naked and non-law-abiding. Except, I’d skimmed the regulations months before and remembered something about journalists being allowed to travel under some license or other and being granted a larger quota of cigars, more than the two I had at least. Which is to say, according to the Trading With the Enemy Act, Cuba is a restricted county and who can go there and what they can do is limited to:

· Journalists and support broadcasting personnel, working on a project

· Official government travelers, traveling on official business

· Persons traveling once a year to visit close relatives, in circumstances of humanitarian need

· Amateur or semi-professional athletes, with a game scheduled, and, well

what do you know:

· Full-time professionals whose travel transactions are directly related to professional research in their areas, provided that their research: (1) is of a noncommercial academic nature, (2) comprises a full work schedule in Cuba, and (3) has a substantial likelihood of public dissemination.

Could that possibly include a couple of professors doing research and seeking to build up their university’s foreign study program, plus a writer gathering local color for a novel? But we didn’t really have these stark restrictions and authorizations committed to memory; we didn’t have to, we were on some other license, we thought. So we muttered and stumbled and must have contradicted ourselves in multiples of three.

Each of us stood at a waist-high counter opposite our own custom’s agent, pulling out our laundry and damp bathing suits and tawdry mementos—the crammed aftermath of nine days of travel. We had to place each item of our tumped-out bag in another pile and answer questions about it.

Mary, who is beautiful and serene anyway, got bored with the whole process and parked one hip up on her side of the counter, to chat with her agent. Like, they were both just going through the routine and soaking up the time with travel talk. He’s telling her how emotional and opinionated these people are, Latin blood you know, but the Cubans are an extreme case, hot-headed bolshies, and she’s replying with where we went, what we saw—collective farms, museums, the university, buildings, the beach, the schools…

“You know they farm their kids out,” he says.

“No…”

“Oh yeah. They take ‘em away from their parents at age five and send ‘em to special schools. Where they brainwash ’em.”

“Where are you getting this stuff?”

“Oh, we go down to Miami for special training.”

And my guy, poking at my last wad of singles with his rubber-gloved hand, says, “Lucky you weren’t robbed in the airport, they’re all thieves.”

“They’re poor, all right,” I say. “Everything costs just a dollar.”

“They can’t make nothing work, economy’s in shambles.”

“Yeah, the embargo’s killing them, like, you know, aspirin.” Pencil sharpeners, bicycle chains, scotch tape, toilet paper, spark plugs, screen door hooks, muffin tins, grommets, eye glass rims, dump trucks, fishing tackle, you name it, they’ve had to invent it out of scraps. “It’s made them very handy,” I say.

“Oh, yeah, best in the world. Those jineteros’ll rob you blind.”

Criminal penalties for violating the Regulations, which are enforced by the Department of the Treasury, range up to 10 years in prison, $1,000,000 in corporate and $250,000 in individual fines. Civil penalties up to $55,000 per violation may also be imposed.

I couldn’t take my quarter million dollar t-shirts seriously—isn’t the penalty the same for copying videotapes?—until a year later when the actual assignment of the penalty phase—was there a trial, I don’t seem to remember one—arrived on, how coincidentally, September 11, 2002. Rick and Mary and I are each being fined $5000 and me an extra $250 for the black and white Che Guevara t-shirts and miniature decorative fork. I will take los hijoputas (the mf fascist SOBs) all the way to the Supreme Court if I can. They’ve already offered to settle for a reduced $2900, part of the routine I think, if you don’t cave to the first year’s intimidation and pay your initial penalty pronto. Most traffickers with the enemy do, though Ry Cooder (Buena Vista Social Club) is still fighting a $25,000 penalty.

Like Ry, we also declined to settle. We weren’t being anti-American (we just wonder about our leaders). In fact, we’re intensely American, with coveted constitutional rights to travel to Hanoi and Bagdad and Mogadishu, but not Cuba, listed by the State Department as one of the seven terrorist-sponsored no-no countries, in large part because Assata Shakur still lives there, the Black Panther that escaped the New Jersey State Troopers in 1979 until she defected to Cuba after five years of hiding underground.

“Probably have to confiscate this stuff,” he says, rummaging through my film, about 20 mini-video cassettes.

“My film? I’m a journalist! That’s my story, my proof!”

“I’ll see,” he says.

Turns out, they returned everything that day, but I kept my video of Cartaya singing his anthem secure in my left armpit until we were at dinner in the airport.

Conversation was not that much about our detention: we thought it had ended there. We would email the students, suggest they be vague about what countries they’d been in; many were going back through Canada anyway, perfectly legal.

School started. The trip, my Cuban family, my jinitero whom, alas, romantic that I am, I did not tip,—it would have spoiled the feeling; the sun-bleached pastels of buildings and country side, the farms, professors, doctors, students, merchants, streets alive with music and familiar passers-by; the ‘50s cars (that I could identify as fast as the Cubans), the ice cream palace, the movies, the German and Japanese and Canadian tourists; the taxi rides, the beautiful women, the shirt sleeves, my love, my longing, my excitement, my Spanish, and my seriously bruised butt from 10 days of bicycling all over the city . . . all faded, healed over. But I had my notes, didn’t I, and I had my film.

And when one day I got Cartaya #3 down from the shelf to make a copy for Mary who was doing something apposite in one of her courses, and cued it to his singing the Cuban nation anthem with another moncadista and their two wives, I got instead school children in uniforms reciting I’ll never know what. What the fu’?

Ohmygod. It came to me: I’d rewound it to show Cartaya to my Cuban family, been side-tracked by the arrival of more of their friends who wanted to see el professor norte americano, and next day in a hurry, had grabbed everything, caught my ride, and began taping as soon as I got there, right over Cartaya. The interview is there, but not the song. The words, but not the music.

So, I have to go back. And all you Bushies and Shrubs, and clown-faced if not buffoon-minded Senator Lieberman, and all you people who signed on to the bottom of all the threatening documents from the United States Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Affairs, if you really want to bring down the Castro regime, let me go back. Let us all go back.

It’s really simple: Let America in. We will corrupt them so fast it won’t even be a sucking sound. Not the whoosh of a giant scythe, as you imagine, but more a gargantuan ke-ching, the fatidic stroke of the global cash register.

Published in: Studies in Travel Writing, Special Issue: Travel Writing and Cuba, Edt. Peter Hulme, Volume 15, Issue 4, Dec. 2011