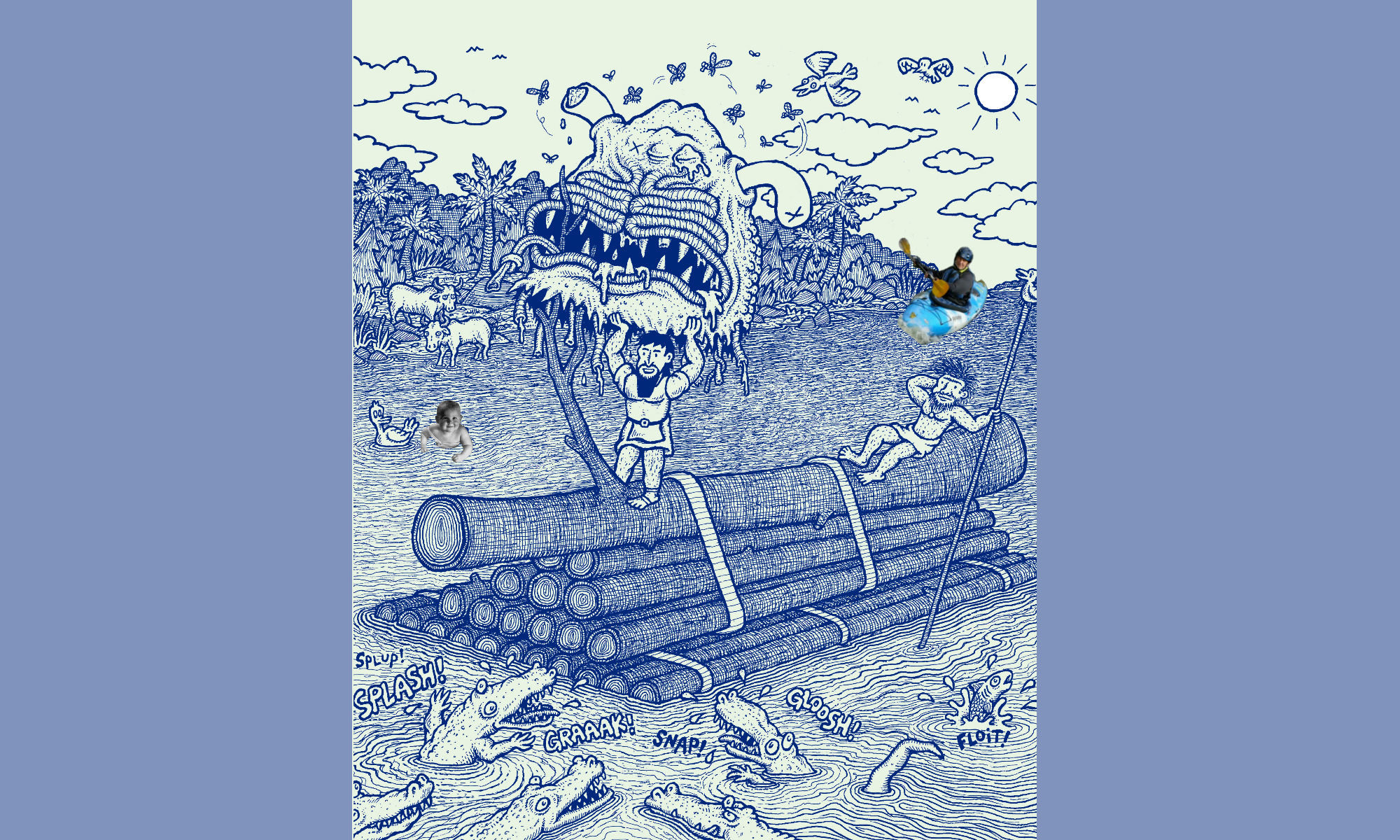

Do you see those musical notes in the drawing above? Goofy Guy is whispering music notation.

And you are familiar with the notation for a musical rest, on a page of sheet music, yes? There are quarter rests and half rests and full rests–no sound, total silence smack in the middle of the piece where the mark is, lasting for an invisible beat or two (depending on the time signature).

Ok, here’s the big secret:

First of all, you need to internalize the fact that a comma is just a notation on the page that represents a brief pause in the reading. (beat, beat…) Whereas a period represents a longer pause, and a fresher start.

Below, read the word ‘beat’ out loud, in order to represent orally the moments of silence that a comma and a period stand for. The sentence and the fragment come from the paragraph just above:

Out loud, now:

First of all , you need to internalize the fact that a comma is a just a notation on the page that

(beat)

represents a brief pause in the reading . Whereas a period represents a longer pause , and a

(beat, beat) (beat)

fresher start . (Beat, beat, take a breath and: ) Below , (beat) read the word ‘beat’…and so on.

We could use a lot of things to represent this (meaningful) pause in the reading of a sentence. If you play the flute, for example, you’ll find in the beginner’s books that they use a raised comma to mark where you should take a breath:

, , ,

Twee twa dee tee twee twee toooooo teka tee teeka tee ta tee ta ta teee (whew!)

Or, we could use something handy on the keyboard like, say, s/ash /ines. Read aloud the comma and the period we used in the example above//out loud//and again now in the following excerpts: ////

First of all //you need to internalize the fact that a comma is a just a notation on the page

that represents a brief pause in the reading //// Whereas a period represents a longer pause //

and a fresher start /////

The secret of the comma is that it’s all just a matter of sound and silence notation. Commas are writers’ and printers’ marks telling the reader how best to read the text, sometimes for the sake of clarity, sometimes for niceties of meaning.

Onceuponatimeyouknowtheydidntputspacesbetweenthewordsmuchlesscommasforpauses. ANDACTUALLYTHOUGHIDONTKNOWIFITSANYWORSETHEYWROTEALLINCAPITALLETTERS

Well, do we have any other marks like this, that aren’t sounds but nonetheless affect the voice and the meaning? Yes, we do.

The ? , as you know, is another mark telling you to do something with your voice: it says, Make your voice go up at the end here, does it not ?

And the ! is like the judge’s gavel–pow ! [Generally, watch out for the ! in your writing. One good piece of advice is to use the exclamation point only when the word or line itself is stronger than the mark,

like WHACKO! ]

Final exam time.

Figure out how to fill out

the blue book or pick one [Art: blue book cover]

up off the floor somewhere,

put down a pseudonym and

a bogus SS#, and answer the

following question in one minute.

If you finish early, go right on.

The Question: If the ! and the ? both (purely

by convention) cause voice changes in the reader,

what voice change could the , be said to cause?

Helps: 1) , = comma

2) Think of the Paul Simon song, about the sounds of ____________ .

I know I promised no RULES, but if you’d like some help from yourself in your everyday punctuation, READ THE BLOODY THING ALOUD! Where you find yourself pausing/// that’s a place to think seriously about flicking down a comma//or slash lines if you can get your reader to go along//or a flowery doodle or something ////

Now, to some nitty gritty about the first three sets of common comma mistakes listed on the Table of Contents in the home page. And a change of color to go with a change of pace.

Items (a), (b), and (c) in the Homepage’s Contents are all covered by pretty much the same

“rule,” which is, you surround all those irritating little stops like yeses and no’s and wells and uh’s and oh’s, and people’s names when you name them–right , Charley?–you set them all off with commas.

Aids: “to set off” means to surround. Set off with commas means put one at the head and one at the tail. You can hear the pauses at the head and the tail if you’ll read it aloud: Well, no, John, not now. Oh, maybe later, but you, John, especially you–uh, what was I going to say?

Once more for the road: all those little hitches in a sentence, which have no place to hide if you’ll read them out loud, those things like expletives, speech dysfluencies (uhh.., er.., duh..), calling someone by name directly (referred to as ‘nouns of direct address’), they all have to be surrounded by commas or they won’t read right: WellnoJohnnotnow. OhmaybelaterbutyouJohnespeciallyyou is not how you want that line read, but it’s what you’re forcing an experienced reader to reproduce in their head, if you don’t tell them where to pause with your commas. So, besides creating a bad read out there, of your own precious thought and expression, you’ve also got someone thinking you’re stupid.

Maybe not stupid, but… [Art.Kevin]

An uneducated, unlettered, inexperienced reader. Not very literate. Why read them if I don’t have to?

That’s what goes on consciously or unconsciously in an experienced reader or

writer when you jam all the sense together and leave out the rests.

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,

, ‘ All those little words, with rests in front and back of ‘ ,

‘ , them? You set them off (which means surround) with ‘,

, commas.* ,

‘ , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,

(a) Well//John//I don’t really think so.

Well, I don’t really think so either, really.

John, do you think so? John? Oh, damnit, would

someone please give John a gentle smack?

(b) No, I’m not going to do that. Yes, I care about my

grade, but John is bigger than I am.

(c) Uh, he’s bigger than I am, too. Why don’t we just,

you know, leave him here.

* Department of the screamingly obvious:

If the word you’re surrounding with commas comes at the very front or very end

of a sentence, then you use the period or the capital to complete its surroundings:

No, this isn’t quite right, JohN.

Yes, no, uh, too, well, unh unh, yeah . . . These are the ones were talking about. They all get set off

(set off = surround) with commas. Yes, we have no bananas. You do, too! No, uh, I’m sorry, but we’re competely out. We can’t even see them, much less have any!

And then when you call someone by name–when you address them–in the text, directly, then they get surrounded with commas, too. If you’ll just listen, you’ll hear that you’re putting pauses around the name addressed, Jack, and you’ll hear that that is different from just using the name to talk about the person in the 3rd person pov:

John, are you with me? (John is never with us.)

We’d like for you, John, to at least smell the coffee. (We’d love it if John would only

wake up and smell the coffee.)

See the pauses around John when he gets spoken to? And those pauses have to be indicated with something, and the convention is: commas. Ok, babe, got that? Whether it’s a “noun of direct address” or a “proper noun of direct address,” it’s going to have those commas surrounding it, front and back. Whether you’re talking to your little baby doll or to Madame TaraShea, if you talk to them directly, person to person there on the page, then you pause fore and aft: So listen close, baby doll, and then I won’t have to call you TaraShea. Tara, are you listening? Hey, you. You with the feather. Come on, TS, help me out here.

Well, that’s enough on these little guys. Right, dear reader?

[Kevin art. Sleeping

Drodoo, snoring.]