I promised no rules, but if I could give you one rule that solved about 80 to 90% of all your

other comma dilemmas, a rule totally consistent with the put-a-comma-where-you-pause-

when-you-read-it-aloud rule (see Secret of all Commas for that one), but an enhancement of that

rule giving you about 190% assurance of no comma mistake, would you live through the below

lesson so you have the background for the rule to make sense?

The “rule” has to do mostly with introductory adverbial clauses, but it also covers adjectival phrases

and in fact all introductory phrases or clauses that can be followed by a comma. Occasions like these

following sentences about one of my favorite Butch-Cassidy-and-Sundance teams–Enkidu and

Gilgamesh, from the Babylonia Epic of Gilgamesh (circa 2000 B.C.).

Although Enkidu and Gilgamesh have just come from killing a huge monster , they are not having

an easy time of it with the Bull of Heaven.

Grabbing onto the bull’s horns , Enkidu tries to lower the head so Gil can get a clear bull-fighter’s

thrust down through the shoulder blades.

While the heroes battle with the bull , the goddess Ishtar is off rubbing her hands in glee, expecting

to be fully revenged for Gil’s insults.

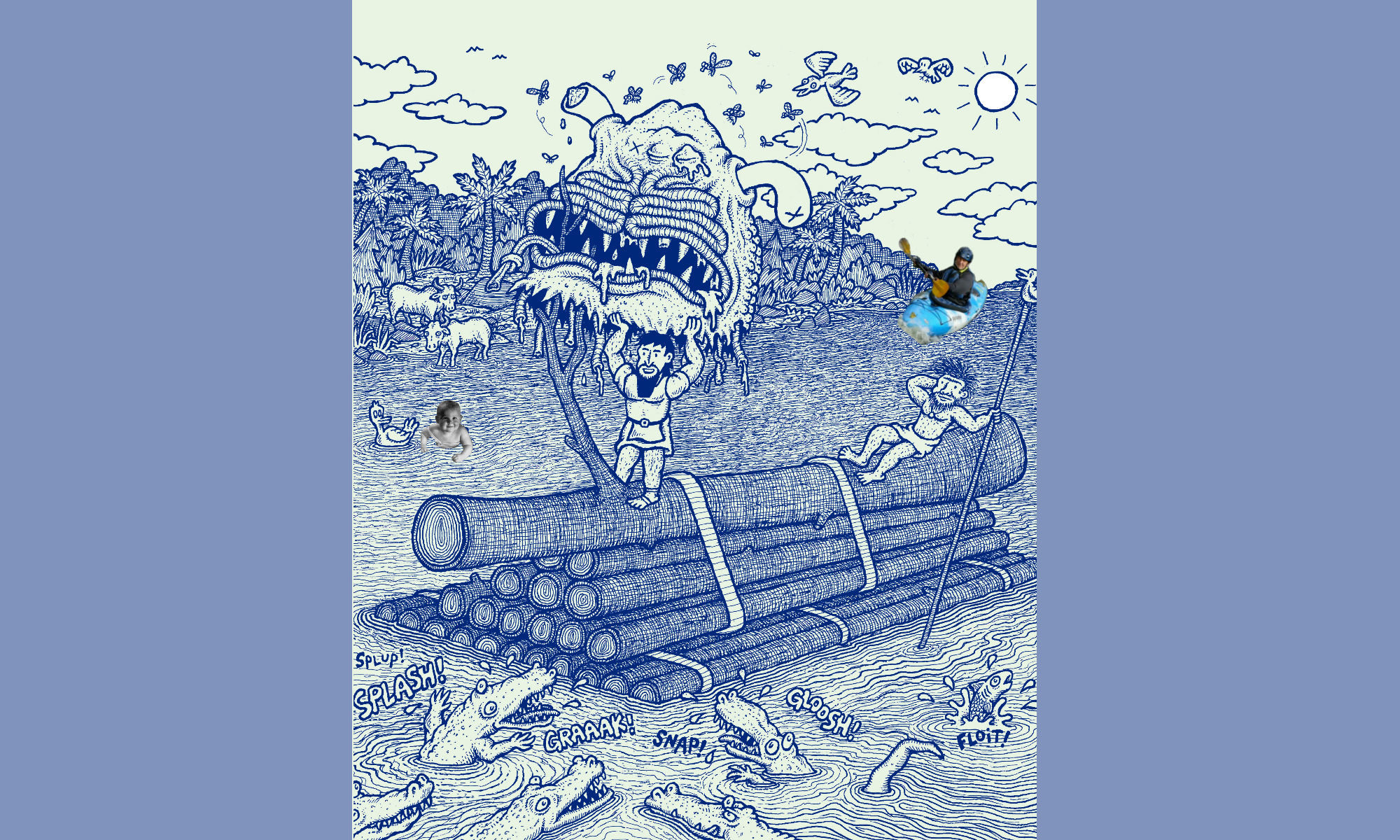

To make this Bull of Heaven truly imposing , the artist has drawn it breaking the frame line.

Because we’ve strained your attention span here (speaking of insults) , we will now give you

a graphic representation of the battle with the Bull of Heaven.

Pretty cute, eh? So stick with us; more to come after you do battle with the following terminology:

phrase, clause, introductory, verbal, verb . (Also finite and subordinate. Sorry!)

Here’s the “rule,” which is really two rules packed into one:

i p c v v ,

stands for:

Any introductory phrase with a verbal, or clause with a verb, in it, can always be followed

by a comma. You’ll never be wrong if you put the comma in. 100% non-wrong.

Any introductory phrase or clause, with a verbal or a verb in it…slap down the comma

and you can’t go wrong. Enkidu and Gilgamesh, who took on far worse challenges than that, never ever had that kind of assurance. Check out what’s been going on while we’ve been working here:

All we need now, besides pick up the pieces, is to be sure about what a verbal is, right? Let’s assume you know “verb”…all those words that express action: express, need, is, know, eat, fight, snort, aim, gore, beware, battle, kill, strain, have, thrust, zzooop, yoink, skreee, go, take, wait, mate, hate, crap, clap, slap….to name a few from the immediate environment, are all verbs. They’re words that name an action, as opposed to a thing or an idea. So, to move on…

Well, wait. What’s the difference again between a main verb and a subordinate verb?

Main verb = it can stand all by itself, it’s independent of any other verb. I say. say is the main verb. Enkidu zzoooped through the air, clutching the bull’s horns. zzoooped is main verb.

The bull yoinked Enkidu like beaten chaff, while his back hooves skreed the ground.

yoinked is the main verb; skreed is a subordinate verb, made subordinate by while.

Subordinate verb = it’s not the main verb. I say that you should already know this. should know is a verb all right, but it won’t stand by itself: That you should already know this. is not something you can whisper even to your significant other right off the top. It’s subordinate to something main.

Ok for subordinate, ok for introductory…how about adverbial?

There are loads of introductory adverbs, like because, when, while, whenever, since, as, however, as soon as that force the verb they introduce, force it into a subordinate (to the main verb) position:

Gilgamesh insulted Ishtar because he knew what she did to all her lovers.

When Enkidu got hold of the bull’s tail, he got a big surprise.

As soon as the bull was dead, Ishtar went bawling on the ramparts. Woe is Ish.

Since these subordinate clauses, introduced by adverbs (when, while, as, ungh, etc.)

all tell you more about the main verb . . .

Gil insults Ishtar because…

Enkidu gets his surprise when…

Ishtar goes bawling as soon as…

Enkidu goes Ungh!! and the bull goes Graahgooahh!while they went round.

…that is, they modify the main verb, telling you the when or why or how about it, then they are adverbial clauses, since adverbs, including adverbial clauses, modify verbs (also adjectives and other adverbs, but let that go for now). And as we’ve seen, these verbs introduced by these adverbs are subordinate to the main verb.

As soon as the bull was dead, Sally! (You can’t say that and make full sense.)

As soon as the bull was dead, we chowed down. (You can say that, particularly if you’re a vulture.)

But here, the bull isn’t dead just yet:

And the rule runs in part:

Any introductory clause with a verb in it, can always be followed by a comma. If the clause is short

and really really clear, then you can skip the comma. But you’ll never be wrong if you insert one.

Never. So forget that correllary for now and just bull your way in with a comma.

Most of these introductory subordinate clauses will be adverbial. There are also phrases that will occur up front, at the head of the sentence, and when they have a verb-like word in them, they can always be set off:

Realizing that a phrase is a group of related words, and noticing that this particular group of related words came at the head of the sentence, he felt quite confident about slapping down his big red comma.

To survive the last week of a semester, one had best have slept the month before.

Those underlined verb-like words are called verbals. They’re verbs, but they don’t have any time attached to them–they aren’t finite, locked into a present or past or future.

He will always survive…that surviving is locked into the future. She survived my tedious lecture… there she’s doing her surviving in the past. But, to survive is what it’s all about, or, To survive a nuclear war, you had best be on the moon… those two survives don’t have any time attached to them: they are infinite. (They are infinitives, in fact.) That’s all that’s meant by finite versus infinite verbs: time.

So, again, any introductory phrase with a verbal in it, can always be followed by a comma.

And that’s a lot like ‘any introductory clause with a verb in it can always ” ” ” ” ‘,

so why not stick the two together:

Any introductory phrase with a verbal, or clause with a verb, put down a comma.

Any introductory phrase or clause with a verbal or a verb in it,

can be followed by a comma.

i p c v v followed by a ,

Enkidu could get vvwhipped around all day, while Gil seeks a vulnerable spot.

Because we don’t have the finished art ready for the next frame, we have to go to the storyboard,

which may not scan so well. ^

And to do that right, I need Mandi anyway.

^

Notice, there’s an introductory adverbial clause, and then an introductory verbal phrase, and both are followed by commas and both are exactly right. Would you write either of them without the comma?

Because we don’t have the finished art ready for the next frame we have to go to the storyboard.

To do that right we need Mandy.

I still put the pause in, at the end of the introductory stuff; so I would definitely put the comma in. But, following my ipcvv rule , I don’t really have to think about it.

As for Enkidu, he gets into some pretty deep doo doo near the end of the battle. Hard to believe it was written 3500 years ago…it looks so comic-booky, but doo doo was always funny, I guess–to some.

(Like father like son!)

[Kevin art: Enkidu at the

tail of the bull, etc.]